Southern Exposure

Bachelor's Retreat

An Historic South Carolina Community Like No Other

An Historic South Carolina Community Like No Other

The Bachelor's Retreat community of Upstate South Carolina, like countless other Southern towns and villages, is rich in history and character. This settlement, however, is further distinguished by how it derived its name and by the number of notable persons who were born or resided there. Prominent individuals with ties to Bachelor's Retreat, located in present-day Oconee County (formerly the Pickens District until 1868), include Confederate officer Captain Aaron Shannon Cole (who was born there in 1837) and former U. S. Congressman J. Gresham Barrett (b. 1961) who spent much of his boyhood at one of the community's last remaining vestiges---the old McWhorter farmstead. At first glance, today's Bachelor's Retreat might appear to be just another rural neighborhood with a few surviving old houses. Nonetheless, a brief assessment of its past provides a realistic vignette of the Old South in which neither the plantation living romanticized in many fictional works nor the stereotypical backwoods Southerner are present.

Beginning with the Verners

The Verners were among the first families to settle the area known as Bachelor's Retreat. Without them, the community might have been given another name or might not have existed at all. John Verner Jr. (1763-1853), a North Carolina native, served in the American Revolution, fighting at Cowpens and Kings Mountain. Following the war, he acquired a number of large tracts of land, including one from South Carolina Governor Arnoldus Vanderhorst. It was on this property on Choestoe Creek that he established a large plantation and owned numerous slaves.

With his first wife, Jane Edmonson, Verner Jr. had two boys and a girl. While tutors educated the Verner children, Rebecca Dickey (who would later become Verner Jr.'s second wife following the death of Jane) was hired to teach the offspring of the slaves in the plantation school.

The Verners were among the first families to settle the area known as Bachelor's Retreat. Without them, the community might have been given another name or might not have existed at all. John Verner Jr. (1763-1853), a North Carolina native, served in the American Revolution, fighting at Cowpens and Kings Mountain. Following the war, he acquired a number of large tracts of land, including one from South Carolina Governor Arnoldus Vanderhorst. It was on this property on Choestoe Creek that he established a large plantation and owned numerous slaves.

With his first wife, Jane Edmonson, Verner Jr. had two boys and a girl. While tutors educated the Verner children, Rebecca Dickey (who would later become Verner Jr.'s second wife following the death of Jane) was hired to teach the offspring of the slaves in the plantation school.

Photograph Courtesy of the Collection of the U. S. House of Representatives

Former U. S. Congressman J. Gresham Barrett

With Rebecca, Verner Jr. sired eleven more offspring, seven of which were boys. Several of the sons remained single long enough for the farming section to earn the name Bachelor's Retreat. While two sons, John A. Verner and David D. Verner (described as "eccentric"), were bachelors for life, two other boys, Ebenezer Pettigrew Verner and Lemuel H. Verner, did eventually marry (but supposedly at older ages than was common at the time for newlyweds).

One interesting fact regarding Rebecca Dickey Verner (1774-1849) is that she was adamantly opposed to slavery. She is said to have strongly discouraged her husband from owning slaves and openly expressed her disdain for slavery. In his unpublished autobiography, Samuel Phillips Verner stated that his ". . . grandmother, Emily, brought slaves into the family in larger numbers than [great] grandmother Rebecca got them out."

In spite of his wife's protests, sadly, it appears that Verner Jr. considered slaves (liquid assets at the time) a necessity on his large, working plantation. However, Verner Jr.'s benevolence is plausible in his desire for the slave children to be educated and in his will (in which he requested that his slaves be allowed to choose their masters among his heirs).

Today, much evidence of the Verner plantation remains on the farm of Carolyn Martin, widow of Hugh Martin. Though expansive by modern standards, the 285-acre Martin farm is only a fraction of what the Verners originally owned. A brick house stands where the Verner residence was once located. An ancient Mulberry tree in the backyard has grown on the property since well before the last Verners occupied the farmstead. An intriguing Verner artifact is a hand-hewn rock Hugh Martin moved from one section of the farm to the front lawn, relying on a trusty tractor and the assistance of a hired hand. Hollowed out so that it might hold water, the slave blacksmiths are said to have used the water-filled stone reservoir to temper metal. The only remaining portion of the Verner house can be found across the road from the Martin residence where it now serves as a hay barn. Nearby are the graves of John Verner Jr. and his second wife, Rebecca. Yards from their graves is the slave cemetery.

When Cotton was King

The Verners were not the only family to originally occupy Bachelor's Retreat. Others, just to name a few, included the Ballengers, Dicksons, McClanahans, McWhorters, Martins and Sheldons. Even John Miller III (1794-1876)---whose famous grandfather, John Miller, came to Charleston from London in 1783, published South Carolina's first daily newspaper and established Miller's Weekly Messenger in Pendleton, South Carolina---resided at Retreat. Primarily agricultural, this community was home to a number of farmers whose chief crop, of course, was cotton.

The 1860 census bears out that the wealth of Ebenezer Pettigrew Verner, 44 at the time, easily surpassed all of the other residents. His real estate holdings, worth over $20,000, and personal estate, worth $47,300 (a significant amount of money in 1860!), for example, far exceeded the still significant $1300 worth of land and $550 personal estate recorded by a neighboring farmer, 69-year-old Joseph Lyles.

More than a wide place in the road, Bachelor's Retreat was certainly a vibrant, thriving locale, but it was never incorporated as a town. Congressman Barrett's late father, Charles G. Barrett (1916-2005), in his True Stories of the Old South, a book of personal recollections and poems he published less than a year prior to his death, explained that Bachelor's Retreat "boasted a post office (franchised in 1812), a general store, whiskey dispensary, cotton gin, a water powered (bread) grain mill, an academy, a school house, etc., not available in other surrounding settlements and frontier communities."

In spite of his wife's protests, sadly, it appears that Verner Jr. considered slaves (liquid assets at the time) a necessity on his large, working plantation. However, Verner Jr.'s benevolence is plausible in his desire for the slave children to be educated and in his will (in which he requested that his slaves be allowed to choose their masters among his heirs).

Today, much evidence of the Verner plantation remains on the farm of Carolyn Martin, widow of Hugh Martin. Though expansive by modern standards, the 285-acre Martin farm is only a fraction of what the Verners originally owned. A brick house stands where the Verner residence was once located. An ancient Mulberry tree in the backyard has grown on the property since well before the last Verners occupied the farmstead. An intriguing Verner artifact is a hand-hewn rock Hugh Martin moved from one section of the farm to the front lawn, relying on a trusty tractor and the assistance of a hired hand. Hollowed out so that it might hold water, the slave blacksmiths are said to have used the water-filled stone reservoir to temper metal. The only remaining portion of the Verner house can be found across the road from the Martin residence where it now serves as a hay barn. Nearby are the graves of John Verner Jr. and his second wife, Rebecca. Yards from their graves is the slave cemetery.

When Cotton was King

The Verners were not the only family to originally occupy Bachelor's Retreat. Others, just to name a few, included the Ballengers, Dicksons, McClanahans, McWhorters, Martins and Sheldons. Even John Miller III (1794-1876)---whose famous grandfather, John Miller, came to Charleston from London in 1783, published South Carolina's first daily newspaper and established Miller's Weekly Messenger in Pendleton, South Carolina---resided at Retreat. Primarily agricultural, this community was home to a number of farmers whose chief crop, of course, was cotton.

The 1860 census bears out that the wealth of Ebenezer Pettigrew Verner, 44 at the time, easily surpassed all of the other residents. His real estate holdings, worth over $20,000, and personal estate, worth $47,300 (a significant amount of money in 1860!), for example, far exceeded the still significant $1300 worth of land and $550 personal estate recorded by a neighboring farmer, 69-year-old Joseph Lyles.

More than a wide place in the road, Bachelor's Retreat was certainly a vibrant, thriving locale, but it was never incorporated as a town. Congressman Barrett's late father, Charles G. Barrett (1916-2005), in his True Stories of the Old South, a book of personal recollections and poems he published less than a year prior to his death, explained that Bachelor's Retreat "boasted a post office (franchised in 1812), a general store, whiskey dispensary, cotton gin, a water powered (bread) grain mill, an academy, a school house, etc., not available in other surrounding settlements and frontier communities."

The Grave of John Verner Jr.

A small Verner family cemetery is located on the 285-acre farm of Mrs. Hugh Martin. The current Martin residence is located where the main farmhouse of John Verner Jr. once stood. The graves of Verner Jr., his wife, Rebecca, and that of a Verner child are located across the road just yards from the slave graveyard where mostly unmarked stones identify the locations of slave graves. Recognizing his service in the Revolutionary War, a small marker from the Walhalla chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) stands near the headstone of Verner Jr. (above).

The Grave of Rebecca Dickey Verner

Mrs. Martin indicates that this ancient mulberry tree has been one of the most photographed features of her property. Passersby have actually stopped in, seeking permission to take a snapshot or two!

Hollowed out by hand, this stone was filled with water and is said to have been used by the Verner slave blacksmiths to temper metal. Arguably, it could have been a watering trough for livestock.

The Verner Genealogy

John Verner (1725-1798) was the father of John Verner Jr. (1763-1853).Of his 14 children, three of Verner Jr.'s offspring included the bachelor sons, John A. Verner and David D. Verner.

Another Verner Jr. son, Ebenezer Pettigrew Verner (1816-1891), was the father of William Henry Verner (1846-1900), a Tuskaloosa, Alabama, professor and founder of the Verner Military Institute; Charles Bell Verner (1867-1937), a Tuskaloosa attorney and Alabama legislator; and John Samuel Verner (1849-1912), a South Carolina legislator.

John Samuel Verner's offspring included Rev. Samuel Phillips Verner (1873-1943), noted African explorer and missionary, and Dr. Lucy Plummer Verner, reportedly the first woman ever to be graduated from the Mayo Clinic.

Retreat Presbyterian Church

Like virtually every other Southern community, faith played a key role in the lives of Bachelor's Retreat residents. Though the Retreat Presbyterian Church was organized in 1851 by the Rev. William H. McWhorter (1811-1898) with 19 members, records show that worshipers had previously attended roving meetings in which services were held on a house-to-house basis. Interesting to note, McWhorter served as a commissioner to the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia in 1841 at a time when Southern representation at the meeting was generally less common because of the distance and prohibitive travel expense. A supporter of the Confederacy, McWhorter had three sons who fought in the Civil War, one of whom was killed in battle. The graves of Rev. William and Margaret McWhorter are located in the Retreat church cemetery.

On October 1, 1968, the Piedmont Presbytery officially dissolved the church. Records were transferred to the Presbyterian History Foundation in Montreat, North Carolina. Though regular worship services are no longer held at Retreat Presbyterian, the church is the site of a reunion each third Sunday in October. Featuring special music, a sermon and a covered dish meal, the event draws a sizable crowd from several states. Folks with Retreat connections and an inner sense of nostalgia come to reminisce and fellowship. Coordinated for years by Mrs. Dorothy Dickson Abbott, wife of Marshall Abbott, CEO of the family-owned Bank of Westminster, the service is now organized by church historian Carla Martin. Fondly recalling her childhood, Mrs. Abbott says, "We went to church there as children," but she adds, "We just went there to preaching every other Sunday," referencing the days of circuit preachers.

Hugh Martin, father of Carla, organized the restoration of Retreat Presbyterian in 1979. Laboring tirelessly to maintain the grounds today, his widow, Carolyn, and daughter continue the work he started decades ago.

Like virtually every other Southern community, faith played a key role in the lives of Bachelor's Retreat residents. Though the Retreat Presbyterian Church was organized in 1851 by the Rev. William H. McWhorter (1811-1898) with 19 members, records show that worshipers had previously attended roving meetings in which services were held on a house-to-house basis. Interesting to note, McWhorter served as a commissioner to the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia in 1841 at a time when Southern representation at the meeting was generally less common because of the distance and prohibitive travel expense. A supporter of the Confederacy, McWhorter had three sons who fought in the Civil War, one of whom was killed in battle. The graves of Rev. William and Margaret McWhorter are located in the Retreat church cemetery.

On October 1, 1968, the Piedmont Presbytery officially dissolved the church. Records were transferred to the Presbyterian History Foundation in Montreat, North Carolina. Though regular worship services are no longer held at Retreat Presbyterian, the church is the site of a reunion each third Sunday in October. Featuring special music, a sermon and a covered dish meal, the event draws a sizable crowd from several states. Folks with Retreat connections and an inner sense of nostalgia come to reminisce and fellowship. Coordinated for years by Mrs. Dorothy Dickson Abbott, wife of Marshall Abbott, CEO of the family-owned Bank of Westminster, the service is now organized by church historian Carla Martin. Fondly recalling her childhood, Mrs. Abbott says, "We went to church there as children," but she adds, "We just went there to preaching every other Sunday," referencing the days of circuit preachers.

Hugh Martin, father of Carla, organized the restoration of Retreat Presbyterian in 1979. Laboring tirelessly to maintain the grounds today, his widow, Carolyn, and daughter continue the work he started decades ago.

Bachelor's Retreat Today

In addition to surviving structures like the church and McWhorter house and outbuildings, the house originally belonging to Dr. J. M. and Mary E. Verner McClanahan still stands in Bachelor's Retreat. It has been restored and was occupied for a number of years by Mr. and Mrs. Lee Barrett, he another son of Charles Barrett. Descendants of the original Bachelor's Retreat families are now scattered throughout Oconee County and elsewhere.

In addition to surviving structures like the church and McWhorter house and outbuildings, the house originally belonging to Dr. J. M. and Mary E. Verner McClanahan still stands in Bachelor's Retreat. It has been restored and was occupied for a number of years by Mr. and Mrs. Lee Barrett, he another son of Charles Barrett. Descendants of the original Bachelor's Retreat families are now scattered throughout Oconee County and elsewhere.

Retreat Presbyterian Church

As for the area today, Bachelor's Retreat is simply known as the Retreat community, and its landscape is a mix of old farm houses, mobile homes and modern residences. Fortunately, there are those who are dedicated to preserving the community's priceless tangibles like important landmarks and artifacts. Of equal importance is the wealth of oral histories passed from one generation to the next. These stories ensure that neither the history of Bachelor's Retreat nor its legacy are diminished or forgotten.

Retreat Presbyterian Church Cemetery

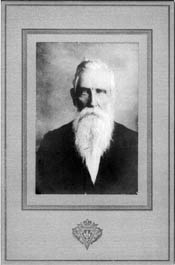

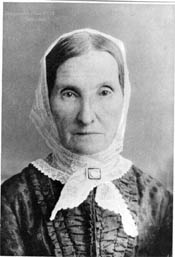

McWhorter Photographs Courtesy of Dr. Patricia Petitt, M.D., a McWhorter descendant residing in the Washington, D.C. area

Rev. William H. McWhorter (March 16, 1811-February 9, 1884)

Mrs. Margaret McWhorter (March 7, 1809-March 6, 1898)

Addenda:

The Samuel Phillips Verner Connection

After suffering significant real estate losses following the Civil War, Ebenezer Pettigrew Verner managed to retain 1200 acres of land located just a few miles from Bachelor's Retreat in present-day Richland. Given the name Coneross Plantation, little evidence of the plantation exists today. Now dissected by highways, including a well-traveled four-lane, former Verner land is now occupied by pine trees, broom sedge and commercial and industrial development. The original Verner house reportedly burned in the late 1800s. A Photographic Tour of the McWhorter Farm

Having desired for quite some time to visit the Barrett property (former residence of Rev. and Mrs. William H. McWhorter) to take photographs, my wish came true in the spring of 2006. My dad had known the late Charles Barrett for years, and I had met Charles's wife, Delavina (Del) M. Ayers Barrett, on several occasions, but I was still a stranger to the family. Since I never would have randomly called Mrs. Barrett or shown up unannounced at her door, I had deliberated at length over how I might arrange a visit.Taking Mrs. Barrett's privacy into consideration, particularly because of her age and her son's political position, I opted to phone the family's real estate management office with plans of speaking with her son, Lee. Instead, I wound up talking with her daughter-in-law, Joyce, and was able to discuss my wishes and inquire whether someone within the family might seek permission from Mrs. Barrett on my behalf to visit the farm and take pictures. Assured that my request would be brought to her attention, I waited several days before receiving a reply.

When the call came granting me permission to photograph the property, I immediately called my friend and Southern Edition contributor Sherry Volrath to share the good news. She wound up accompanying me on my visit to the Barrett farm. Being history buffs, we were both fascinated by the beautiful main house and outbuildings, and the photos resulting from that excursion reveal much about late 19th Century plantation living.

Interestingly, the Barretts had purchased the McWhorter property from Hugh Martin in 1965, four years following the birth of Gresham. The Martins moved just down the road and built a new home on the old Verner plantation.

In October 2006, just months after I visited her residence, Mrs. Barrett passed away. She was 84.

Following are the resulting photographs from my May 2, 2006 visit to the Barrett/McWhorter property:

At Coneross, an Ebenezer Pettigrew Verner son, John Samuel Verner (1849-1912), resided and raised a family of his own. John Samuel Verner's children included Reverend Samuel Phillips Verner (1873-1943), the noted African explorer, amateur anthropologist and missionary, and anesthesiologist Dr. Lucy Plummer Verner, the first woman ever to be graduated from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Articles by Samuel Phillips Verner appeared in The Atlantic Monthly and Popular Science Monthly. He also authored Pioneering in Central Africa (Richmond, Virginia: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1903) and Mukanda Wa Chiluba-Mikanda Wa Cinina Ne Bwalu Bwa Fidi Mukulo, a book written in Tschiluba (a native African tongue) of which the only known remaining copy (of the 5,000 volumes Verner printed at his own expense in 1899) is located at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

Articles by Samuel Phillips Verner appeared in The Atlantic Monthly and Popular Science Monthly. He also authored Pioneering in Central Africa (Richmond, Virginia: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1903) and Mukanda Wa Chiluba-Mikanda Wa Cinina Ne Bwalu Bwa Fidi Mukulo, a book written in Tschiluba (a native African tongue) of which the only known remaining copy (of the 5,000 volumes Verner printed at his own expense in 1899) is located at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

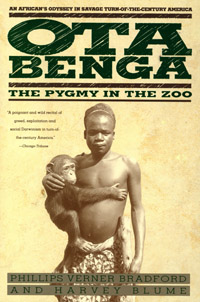

Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992) was written by Phillips Verner Bradford (a grandson of Samuel Phillips Verner) and Harvey Blume.

Samuel Phillips Verner was probably best known for bringing Ota Benga, an African pygmy man, to the United States. Ota Benga and other pygmies were "exhibited" at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair to demonstrate life in the African bush. Thereafter, Verner and Ota Benga returned to Africa to collect artifacts. With plans of selling the collection to the American Museum of Natural History, Verner was bankrupt upon returning to New York, and the Guardian Trust Company seized his artifacts before he could facilitate a sale. Verner returned to South Carolina, leaving Ota Benga in the care of the museum which eventually transferred him to the Bronx Zoo! A big attraction, Ota Benga shared sleeping quarters with an Orangatan, prompting much intense controversy. Thereafter, he lived with one well-meaning individual after another, but Ota Benga grew homesick for his native land. Consumed with hopelessness because it appeared that he might never return to Africa, he committed suicide with a borrowed revolver in Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1916.

Verner married Harriett Dunlap Bradshaw in 1901. With her, he fathered five children. However, a liaison with an African woman residing at a home for orphans had presumably resulted in the birth of at least two children prior to his marriage to Bradshaw. Dr. John C. Crawford, a professor of history at North Carolina's Montreat College at the time, inadvertently discovered Verner's daughter on a trip he made through the Central African city of Luebo in the 1950s. Verner's African daughter had reportedly married a village chief with whom she bore many children.

Verner died on October 10, 1943 and is buried near Brevard, North Carolina, in the Davidson River Cemetery overlooking the French Broad River.

Verner married Harriett Dunlap Bradshaw in 1901. With her, he fathered five children. However, a liaison with an African woman residing at a home for orphans had presumably resulted in the birth of at least two children prior to his marriage to Bradshaw. Dr. John C. Crawford, a professor of history at North Carolina's Montreat College at the time, inadvertently discovered Verner's daughter on a trip he made through the Central African city of Luebo in the 1950s. Verner's African daughter had reportedly married a village chief with whom she bore many children.

Verner died on October 10, 1943 and is buried near Brevard, North Carolina, in the Davidson River Cemetery overlooking the French Broad River.

Presumed slave quarters

The original home of Rev. and Mrs. William H. McWhorter, this property was home to Charles and Del M. Ayers Barrett, late parents of U. S. Congressman J. Gresham Barrett.

Rustic Cabin

One of several barns and outbuildings located on the old McWhorter farm

Store and Post Office

Blacksmith Forge, Horsedrawn Plows and Pulleys

Horsedrawn Cultivators and Plows

Sharpener and Horsedrawn Plow

Author's Note: This article would not have been possible without the hospitality of Mrs. Carolyn Martin (whom I visited on August 5, 2006) and the late Mrs. Delavina M. Barrett (1922-2006) who both permitted me to roam their properties and freely take photographs. Also, telephone interviews with Ms. Carla Martin and Mrs. Dorothy Abbott proved particularly invaluable, and the McWhorter photographs from Dr. Petitt certainly enhanced this story. Since the publication of this article, the Abbotts have passed. Dorothy Dickson Abbott (1933 - 2009) passed away some five years before her husband, Marshall T. Abbott (1931-2014). Marking the end of an era, the Abbott-controlled Bank of Westminster was acquired by locally-owned Community First Bancoporation in 2011, becoming a Community First Bank branch. In February 2024, Community First Bank merged with North Carolina-based Dogwood State Bank, leaving only one locally-owned bank in Oconee County, South Carolina: Blue Ridge Bank.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Charles G. Barrett, True Stories of the Old South (Westminster, South Carolina: independently published, 2004).

Phillips Verner Bradford and Harvey Blume, Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992).

Mary Cherry Doyle, Historic Oconee in South Carolina (Seneca, South Carolina: independently published, 1935).

Clara Verner Wallace, Verner Genealogy (Seneca, South Carolina: independently published, 1969).

"Another Great and Good Man Has Passed Away," Walhalla Courier, February 12, 1884.

OTHER SOURCES

Telephone conversation with Mrs. Dorothy "Dot" Dickson Abbott, Westminster, South Carolina, Spring 2006

Telephone conversation with Ms. Carla Martin, Westminster, South Carolina, August 2006

Visit with Mrs. Delavina M. Barrett (1922-2006), Westminster, South Carolina, May 2, 2006

Visit with Mrs. Carolyn Martin, Westminster, South Carolina, on August 5, 2006

Author: Greg Freeman. Published August 18, 2007. Revised September 2, 2008. Revised August 5, 2011. Revised May 24, 2025.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Charles G. Barrett, True Stories of the Old South (Westminster, South Carolina: independently published, 2004).

Phillips Verner Bradford and Harvey Blume, Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992).

Mary Cherry Doyle, Historic Oconee in South Carolina (Seneca, South Carolina: independently published, 1935).

Clara Verner Wallace, Verner Genealogy (Seneca, South Carolina: independently published, 1969).

"Another Great and Good Man Has Passed Away," Walhalla Courier, February 12, 1884.

OTHER SOURCES

Telephone conversation with Mrs. Dorothy "Dot" Dickson Abbott, Westminster, South Carolina, Spring 2006

Telephone conversation with Ms. Carla Martin, Westminster, South Carolina, August 2006

Visit with Mrs. Delavina M. Barrett (1922-2006), Westminster, South Carolina, May 2, 2006

Visit with Mrs. Carolyn Martin, Westminster, South Carolina, on August 5, 2006

Author: Greg Freeman. Published August 18, 2007. Revised September 2, 2008. Revised August 5, 2011. Revised May 24, 2025.

Copyright

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

All materials contained on this site, including text and images, are protected by copyright laws and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. Where applicable, use of some items contained on this site may require permission from other copyright owners.

Fair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.

Contact Greg Freeman or SouthernEdition.comFair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.