Southern Exposure

Forty Years Later

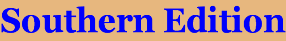

Remembering Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Remembering Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose dynamic leadership, charisma and stirring speeches earned him iconic status, devoted the last thirteen years of his short life to the civil rights movement. He fought vigorously for the cause he held dear without ever raising a fist, even receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 for his pacifistic activism. And he was a lofty dreamer, whose assassination on a balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on April 4, 1968, proved to be one of the nation's worst nightmares in a tumultuous era that had already witnessed the social blight of the American South, the start of the controversial Vietnam War, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and the subsequent counterculture of America's youth.

Early on, King sensed an innate calling to serve others, but it is doubtful that he could have ever envisioned the capacity in which he would serve. In a King biography he penned for the New Georgia Encyclopedia, John A. Kirk, an award-winning author and professor of U. S. History at the University of London (United Kingdom), explained, "King first considered studying medicine or law but decided to major in sociology. He ultimately found the call to the ministry irresistible, however."

In 1954, King and his wife, Coretta Scott, whom he had married the year before, relocated from Boston (where they had met in college) to Montgomery where King would fill the vacated pastoral position at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Though he had not anticipated playing a major part in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which resulted from Rosa Parks' refusal to surrender her bus seat to a white passenger, King permitted meetings to take place at Dexter Avenue that led to the formation of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). At the urging of others within the African American community, King wound up leading the organization.

In 1954, King and his wife, Coretta Scott, whom he had married the year before, relocated from Boston (where they had met in college) to Montgomery where King would fill the vacated pastoral position at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Though he had not anticipated playing a major part in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which resulted from Rosa Parks' refusal to surrender her bus seat to a white passenger, King permitted meetings to take place at Dexter Avenue that led to the formation of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). At the urging of others within the African American community, King wound up leading the organization.

Photograph by Dick DeMarsico

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

(Courtesy of New York World-Telegram and Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection of the Library of Congress Print and Photograph Division, Washington, D.C.)

(Courtesy of New York World-Telegram and Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection of the Library of Congress Print and Photograph Division, Washington, D.C.)

Little did King know that his initial stance in Montgomery would catapult him to the forefront of the unfolding civil rights movement in the United States---a cause for which he would become internationally known. Along the way, a diverse group of supporters---ranging from entertainers and politicians to community leaders and disenfranchised college students---openly expressed their support for the movement. Though some boldly participated in King's widely publicized marches, others such as world-renowned evangelist Dr. Billy Graham sought to transform the nation in circles where they felt their efforts could prove most effective.

In his autobiography, Just As I Am, Dr. Graham recounts the conversations he and King had regarding how they each might reshape the society through their own unique ministries and constituencies. "Early on, Dr. King and I spoke about his method of using nonviolent demonstrations to bring an end to racial segregation," Graham wrote. "He urged me to keep on doing what I was doing---preaching the Gospel to integrated audiences and supporting his goals by example---and not to join him in the streets."

It is apparent, in hindsight, that a combination of actions---ranging from demonstrations by King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to support from prominent politicos such as Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. and the Kennedys to efforts of white religious leaders such as Dr. Graham---roiled the moral consciousness of the nation and prompted unprecedented changes in law and attitudes.

In his autobiography, Just As I Am, Dr. Graham recounts the conversations he and King had regarding how they each might reshape the society through their own unique ministries and constituencies. "Early on, Dr. King and I spoke about his method of using nonviolent demonstrations to bring an end to racial segregation," Graham wrote. "He urged me to keep on doing what I was doing---preaching the Gospel to integrated audiences and supporting his goals by example---and not to join him in the streets."

It is apparent, in hindsight, that a combination of actions---ranging from demonstrations by King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to support from prominent politicos such as Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. and the Kennedys to efforts of white religious leaders such as Dr. Graham---roiled the moral consciousness of the nation and prompted unprecedented changes in law and attitudes.

Reflecting upon the life and profound contributions of Dr. King, various news organizations and print publications recently featured interviews with a number of individuals who had worked alongside King in the struggle for civil rights. While there is much to be learned from those who had, at times, witnessed bigotry and discrimination at its worst and yet saw their diligence and sacrifice foster improvements in integration and equality, I was compelled to interview someone who was neither present during the Montgomery Bus Boycott nor living at the time of King's death.

Savannah native Dr. Raphael Gamaliel Warnock is senior pastor at Atlanta's historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, a congregation formerly pastored or co-pastored by Dr. King, Martin Luther King Sr., A. D. King (Dr. King's brother) and Alfred Daniel Williams (Dr. King's maternal grandfather). During their tenures, Reverend Williams, his son and grandsons championed civil rights and steadfastly pushed for positive social advances.

Under the leadership of Dr. Warnock and his immediate predecessor, the Reverend Joseph L. Roberts Jr., Ebenezer's social and political influence has hardly been diminished in the decades that have followed the civil rights movement. The church continues to make an impact far beyond the confines of Atlanta where its ministry has been going strong since 1886. Past stops made by sitting U. S. presidents as well as recent visits from U. S. Senator Barack Obama and former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee, attest to Ebenezer's national prominence.

So, on April 4, 2008 --the fortieth anniversary of Dr. King's assassination, I was particularly interested in talking with Dr. Warnock. I was curious to know what it might be like to minister to a congregation once led by Dr. King. I was anxious to hear his thoughts on the strides our country has made as a result of the efforts of King and his colleagues. And I was especially interested in hearing his perspective on how we, as a nation, should deal with the remaining racial disparities. After all, a number of issues still divide the races, and prejudice and racism -- though sometimes less overt these days -- are still thriving in some circles.

Reminiscent of Dr. King in many respects, Dr. Warnock is passionately devoted to his calling, well-versed in the scriptures, formally educated and eloquent in speech. His answers prove thought-provoking, reminding us that we all still have a role to play in shaping our country into a nation where true equality, racial harmony and brotherly love abound.

Savannah native Dr. Raphael Gamaliel Warnock is senior pastor at Atlanta's historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, a congregation formerly pastored or co-pastored by Dr. King, Martin Luther King Sr., A. D. King (Dr. King's brother) and Alfred Daniel Williams (Dr. King's maternal grandfather). During their tenures, Reverend Williams, his son and grandsons championed civil rights and steadfastly pushed for positive social advances.

Under the leadership of Dr. Warnock and his immediate predecessor, the Reverend Joseph L. Roberts Jr., Ebenezer's social and political influence has hardly been diminished in the decades that have followed the civil rights movement. The church continues to make an impact far beyond the confines of Atlanta where its ministry has been going strong since 1886. Past stops made by sitting U. S. presidents as well as recent visits from U. S. Senator Barack Obama and former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee, attest to Ebenezer's national prominence.

So, on April 4, 2008 --the fortieth anniversary of Dr. King's assassination, I was particularly interested in talking with Dr. Warnock. I was curious to know what it might be like to minister to a congregation once led by Dr. King. I was anxious to hear his thoughts on the strides our country has made as a result of the efforts of King and his colleagues. And I was especially interested in hearing his perspective on how we, as a nation, should deal with the remaining racial disparities. After all, a number of issues still divide the races, and prejudice and racism -- though sometimes less overt these days -- are still thriving in some circles.

Reminiscent of Dr. King in many respects, Dr. Warnock is passionately devoted to his calling, well-versed in the scriptures, formally educated and eloquent in speech. His answers prove thought-provoking, reminding us that we all still have a role to play in shaping our country into a nation where true equality, racial harmony and brotherly love abound.

Greg Freeman: As senior pastor there at Ebenezer Baptist Church, I'm sure you feel incredibly honored to serve in a church that was the spiritual nucleus of the civil rights movement. How has the work of your predecessors influenced or impacted your ministry at Ebenezer?

Dr. Raphael Gamaliel Warnock: Indeed, it is an honor to serve as senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church---what I like to call America's freedom church, the church of Martin Luther King Jr.---particularly as one who was born after the civil rights movement. Dr. King was assassinated in 1968. I was born in 1969. And so, as we celebrate the fortieth anniversary of his death, in a real sense we are witnessing and indeed -- I and many others, I think -- inviting a new generation of leaders who have benefited greatly from the great sacrifice that he and others made. So, I'm humbled by the opportunity to serve.

Greg: Since the civil rights movement, we know that equal rights have been legislated and blatant discrimination has been made illegal, but I think everyone would agree that you can enact every law in the world but it doesn't necessarily change hearts and minds. Dr. King advocated love and unity, and I tend to think that we really need to be in one accord to achieve true equality. What do you think the Church.....and when I say the church, I'm talking about God's people as a whole.....can do to foster some reconciliation and a sense of oneness? After all, on Sunday mornings we're pretty much the most segregated group of people in the country. So, what can we do as believers to really make great strides?

Dr. Warnock: I would argue that we need both love and law. Love is the supreme principle that drove Dr. King's ministry, but it was a public ministry that sought to transform the society. Somehow, society has to find a way to institutionalize the law of love in its public policy and in its laws. Or else, the weakest in the society will always be at a distinct disadvantage. I think the founders of the country understood that, and they wanted to make sure that no minority would be subject to the tyranny of the majority, that somehow through our laws we would concretize and institutionalize the supreme principle of love.....love which becomes concrete in equal access to public education and health care and all of the resources that all freedom-loving people would embrace. So, that's part of the struggle and a critical part that we must never diminish. The other side of the struggle, as you point out, is the work not only to transform society but also to transform people's hearts and minds. I think there's a way in which those two things feed each other. I think that we reinforce our commitment to love by what we do in terms of our public policy, but then in our homes and in our schools and certainly in our churches we have to reinforce that the scripture is right. Of one blood, God has made all nations to dwell upon the face of the earth. And the power of Martin Luther King Jr.'s voice, the reason it is so powerful even as it rings from the crypt, is that he called us to our highest and our best and he helped us to see in his own words that we are all "caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny." What affects one directly affects all indirectly. If there's any institution that ought to lead in this regard, certainly it is the Church of Jesus Christ.

Greg: Would you say there is any one particular thing or is it a series of things that really should be done to help us see his dream manifested throughout the nation? Some would suggest we need a spiritual awakening or revival. Some might argue for a change in leadership. Others would say we need less apathy among the current leadership. Perhaps we need more legislative reform. What are your thoughts on this?

Dr. Raphael Gamaliel Warnock: Indeed, it is an honor to serve as senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church---what I like to call America's freedom church, the church of Martin Luther King Jr.---particularly as one who was born after the civil rights movement. Dr. King was assassinated in 1968. I was born in 1969. And so, as we celebrate the fortieth anniversary of his death, in a real sense we are witnessing and indeed -- I and many others, I think -- inviting a new generation of leaders who have benefited greatly from the great sacrifice that he and others made. So, I'm humbled by the opportunity to serve.

Greg: Since the civil rights movement, we know that equal rights have been legislated and blatant discrimination has been made illegal, but I think everyone would agree that you can enact every law in the world but it doesn't necessarily change hearts and minds. Dr. King advocated love and unity, and I tend to think that we really need to be in one accord to achieve true equality. What do you think the Church.....and when I say the church, I'm talking about God's people as a whole.....can do to foster some reconciliation and a sense of oneness? After all, on Sunday mornings we're pretty much the most segregated group of people in the country. So, what can we do as believers to really make great strides?

Dr. Warnock: I would argue that we need both love and law. Love is the supreme principle that drove Dr. King's ministry, but it was a public ministry that sought to transform the society. Somehow, society has to find a way to institutionalize the law of love in its public policy and in its laws. Or else, the weakest in the society will always be at a distinct disadvantage. I think the founders of the country understood that, and they wanted to make sure that no minority would be subject to the tyranny of the majority, that somehow through our laws we would concretize and institutionalize the supreme principle of love.....love which becomes concrete in equal access to public education and health care and all of the resources that all freedom-loving people would embrace. So, that's part of the struggle and a critical part that we must never diminish. The other side of the struggle, as you point out, is the work not only to transform society but also to transform people's hearts and minds. I think there's a way in which those two things feed each other. I think that we reinforce our commitment to love by what we do in terms of our public policy, but then in our homes and in our schools and certainly in our churches we have to reinforce that the scripture is right. Of one blood, God has made all nations to dwell upon the face of the earth. And the power of Martin Luther King Jr.'s voice, the reason it is so powerful even as it rings from the crypt, is that he called us to our highest and our best and he helped us to see in his own words that we are all "caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny." What affects one directly affects all indirectly. If there's any institution that ought to lead in this regard, certainly it is the Church of Jesus Christ.

Greg: Would you say there is any one particular thing or is it a series of things that really should be done to help us see his dream manifested throughout the nation? Some would suggest we need a spiritual awakening or revival. Some might argue for a change in leadership. Others would say we need less apathy among the current leadership. Perhaps we need more legislative reform. What are your thoughts on this?

Ebenezer Baptist Church's Heritage Sanctuary

"Papa, Why Are You Crying?"

On September 6, 2003, some friends (including Southern Edition contributors Sherry Volrath and Matt Neal) and I spent the day in Atlanta. Our itinerary included a stop at Ebenezer Baptist Church and the nearby King Memorial. I had been fascinated with civil rights history and the significance of Ebenezer for years, and it was a memorable experience to visit for the first time.

We stood inside the Heritage Sanctuary, now a unit of the National Park Service, in which Dr. King had shared from God's Word on so many occasions. Talking in a church whisper out of reverence and respect, I mentioned the funeral of Dr. King in which everyone from Vice President Hubert Humphrey to Harry Belafonte to Mahalia Jackson had attended. Then, I told them how church organist Alberta Williams King (King's mother) and Deacon Edward Boykin had been gunned down by a black college student in a senseless rampage during a Sunday morning service in 1974.

As we quietly walked around, I noticed a gentleman, perhaps in his late fifties or early sixties, seated in a pew. A black man, he held in his arms a restless toddler who was more interested in running and playing. I smiled at the cute boy as the two of us made eye contact for a split second. Then I noticed the man bowed his head, and I saw tears streaming down his cheeks. Now seated in the man's lap, the inquisitive youngster, neither able to speak in complete sentences nor able to pronounce all of his words correctly, mumbled something and then asked his grandfather why he was crying. In response, the gentleman smiled the best smile he could muster up, said nothing and just pulled the boy close and held him tightly.

I walked away, no doubt, touched by what I had seen in those few seconds, but I couldn't help but wonder what had transpired in the man's life. Had the dagger of racism and prejudice wounded him from an early age? Quite possibly. Had he witnessed firsthand the marches led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or even participated in them as a young man? Perhaps. Had Atlanta and Ebenezer Baptist Church become a Mecca of sorts where he could travel (from no telling where) to reflect and meditate? Maybe.

Regardless, I suddenly felt like a voyeur in a sense. What right did I have to ponder what the man was thinking? And what right did I have to wonder what he had experienced in his life to prompt such an emotional response? I then realized from my own emotional response that the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the symbolism of Atlanta's Sweet Auburn community and its beloved Ebenezer Baptist Church probably evoke different thoughts and emotions for different people. Whether you marched with Dr. King down the streets of Selma, Montgomery or Albany as a young, black college student or you're a white Generation Xer like myself who has merely read of such events, there is much to be learned from it all. If, from our different experiences and through our own unique perspectives, we still can be moved by King's words and sense the profound impact of his life and poignancy of his death when we stroll along Atlanta's Auburn Avenue or pause for reflection within the walls of Ebenezer Baptist Church, we have more in common than once thought. And I think there's hope for us yet. G.F.

We stood inside the Heritage Sanctuary, now a unit of the National Park Service, in which Dr. King had shared from God's Word on so many occasions. Talking in a church whisper out of reverence and respect, I mentioned the funeral of Dr. King in which everyone from Vice President Hubert Humphrey to Harry Belafonte to Mahalia Jackson had attended. Then, I told them how church organist Alberta Williams King (King's mother) and Deacon Edward Boykin had been gunned down by a black college student in a senseless rampage during a Sunday morning service in 1974.

As we quietly walked around, I noticed a gentleman, perhaps in his late fifties or early sixties, seated in a pew. A black man, he held in his arms a restless toddler who was more interested in running and playing. I smiled at the cute boy as the two of us made eye contact for a split second. Then I noticed the man bowed his head, and I saw tears streaming down his cheeks. Now seated in the man's lap, the inquisitive youngster, neither able to speak in complete sentences nor able to pronounce all of his words correctly, mumbled something and then asked his grandfather why he was crying. In response, the gentleman smiled the best smile he could muster up, said nothing and just pulled the boy close and held him tightly.

I walked away, no doubt, touched by what I had seen in those few seconds, but I couldn't help but wonder what had transpired in the man's life. Had the dagger of racism and prejudice wounded him from an early age? Quite possibly. Had he witnessed firsthand the marches led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or even participated in them as a young man? Perhaps. Had Atlanta and Ebenezer Baptist Church become a Mecca of sorts where he could travel (from no telling where) to reflect and meditate? Maybe.

Regardless, I suddenly felt like a voyeur in a sense. What right did I have to ponder what the man was thinking? And what right did I have to wonder what he had experienced in his life to prompt such an emotional response? I then realized from my own emotional response that the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the symbolism of Atlanta's Sweet Auburn community and its beloved Ebenezer Baptist Church probably evoke different thoughts and emotions for different people. Whether you marched with Dr. King down the streets of Selma, Montgomery or Albany as a young, black college student or you're a white Generation Xer like myself who has merely read of such events, there is much to be learned from it all. If, from our different experiences and through our own unique perspectives, we still can be moved by King's words and sense the profound impact of his life and poignancy of his death when we stroll along Atlanta's Auburn Avenue or pause for reflection within the walls of Ebenezer Baptist Church, we have more in common than once thought. And I think there's hope for us yet. G.F.

Photograph courtesy of Ebenezer Baptist Church

Dr. Raphael Gamaliel Warnock, a Savannah native, is the current senior pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Ebenezer Baptist Church's Horizon Sanctuary

Ebenezer Baptist Church's Horizon Sanctuary was dedicated in 1999, and is located across the street from the original building, now known as the Heritage Sanctuary. Long noted for its influence regarding nationally relevant social and political matters, Ebenezer recently welcomed a number of prominent political leaders. On January 20, 2008, U. S. Senator Barack Obama delivered a speech at Ebenezer while on the campaign trail. The following day, former U. S. President Bill Clinton, former Arkansas Governor/presidential hopeful Mike Huckabee, Georgia Lieutenant Governor Casey Cagle and Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin were among a crowd of more than 2,000 in attendance for a special Martin Luther King Day service.Dr. Warnock: Sure, I would embrace all of those things that you mentioned. We certainly need a spiritual awakening, but the true test of authentic spirituality is how it actualizes itself in community. So, the danger of talking about spirituality in abstract terms is that one can wax eloquently about it and live with deep contradictions. For centuries, the American church [went] through many revivals.....the First Great Awakening, the Second Great Awakening and Azusa Street Revival, which was the birth of neopentecostalism.....which is my roots, by the way. Through all of that, most of the white American churches embraced slavery and then segregation and did not see that the two were irreconcilable. So, what we need really is truth telling. We need bold truth telling, the kind of truth telling that alarms the public sometimes when they hear it spoken with such passion and power. But, if people will listen to all of the sermons of Dr. King, particularly toward the end of his life, we will hear again on this anniversary of his death that through his undying commitment to the beloved community he always called us to look beyond ourselves to resist the forces of xenophobia that emphasize the ways in which we are different rather than the ways in which we are very much alike. And, so I would lift up that kind of spirit. I would lift up the kind of selfless leadership that he embodied. He clearly was much more concerned about his calls than himself. He said it best: A man who has not found something that he's willing to die for isn't fit to live. I would say this not only to individual persons but even to a nation.....that a nation would allow itself to die as it were. I don't mean to die physically, but to die unto its imperialistic impulses so that as one beloved community here on the earth all of us can experience abundant life.

Greg: Powerful words, my friend. Like I said earlier, I know you are bombarded with calls today. And I certainly appreciate your taking the time to talk with me.

Dr. Warnock: Sure. It's been my pleasure.

Greg: And I look forward to sharing this with my readers.

Dr. Warnock: Thank you so very much.

BIBLIOGRAPHYGreg: Powerful words, my friend. Like I said earlier, I know you are bombarded with calls today. And I certainly appreciate your taking the time to talk with me.

Dr. Warnock: Sure. It's been my pleasure.

Greg: And I look forward to sharing this with my readers.

Dr. Warnock: Thank you so very much.

Billy Graham, Just As I Am: The Autobiography of Billy Graham (San Francisco and Grand Rapids, Michigan: HarperSan Francisco and Zondervan, 1997).

"Ebenezer Baptist Church," New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 1, 2008: http://www.newgeorgiaencyclopedia.org/

"Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968)," New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 1, 2008: http://www.newgeorgiaencyclopedia.org/

OTHER SOURCES

Telephone conversation with Dr. Raphael Gamaliel Warnock, Ebenezer Baptist Church, Atlanta, on April 4, 2008.

Author: Greg Freeman. Published April 19, 2008.

Author/Editor's Note, January 7, 2021: Since the publication of this article, United States Senator Barack Obama went on to become President Obama, becoming the first African American president in U. S. history, serving two terms. In January 2021, Dr. Raphael Warnock became U. S. Senator Warnock, defeating incumbent Kelly Loeffler in one of two hotly contested and global news-generating senate races, making him the first African-American from Georgia to serve in the United States Senate.

Copyright

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

All materials contained on this site, including text and images, are protected by copyright laws and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. Where applicable, use of some items contained on this site may require permission from other copyright owners.

Fair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com does is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.

Contact Greg Freeman or SouthernEdition.comFair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com does is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.