Magnolia Eden

South Carolina and the History of American Daffodils

Passiflora incarnata, or Passion Flower, is a most intriguing plant, worthy of a place in any southern garden where its beauty and function can be fully appreciated. Not particularly fussy and demanding, the plant tolerates a variety of soil conditions and can thrive in full sun and partial shade. Its elaborate, showy flowers falsely allude to more exotic origins, but this American native is widespread throughout the American South and elsewhere. As if its good looks are not enough, Passion Flower is also a host plant to the beautiful Gulf Fritillary butterfly, making it of particular interest to butterfly enthusiasts.

Utilized by Native Americans and grown by southern settlers, Passiflora incarnata was introduced in England in 1629 and first offered in an American nursery/seed catalogue in 1811 by the Philadelphia-based Landreth Nursery.

A vigorous grower, the perennial Passiflora climbs by tendrils, reaching 10-20 feet. It can also be grown as a ground cover. Blooming between May and September, Passion Flower produces edible oval fruits old-timers often refer to as maypops. Many a southern kitchen has turned out jars of maypop jelly, and some commercial fruit juices available today contain extract from maypops.

While seeds can be retained from the fruits of Passiflora, it is easily propagated by rooting cuttings.

What's in a name?

Named by Roman Catholic missionaries, according to legend, Passiflora is perhaps best known for its Christian symbolism. Hardly referencing eroticism or sexuality, Passion Flower and its various parts represent Christ's crucifixion. There are ten petals for the ten apostles present at the crucifixion, an ovary column resembling a cross, three stigmas for the nails, colored filaments for the crown of thorns, five pollen-bearing anthers for Christ's wounds and coiling vine tendrils reminiscent of whips or scourges.

A Gracious Southern Host

Passiflora incarnata is especially admired by butterfly lovers because it is a host plant to the Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae). Planted in sufficient quantity along with butterfly-attracting plants like Echinacea, Buddleja and Lantana, Southern gardeners are almost guaranteed to witness nature at work as Gulf Fritillaries are drawn to the garden to lay their eggs on the various parts of Passiflora. The resulting spiny larvae feed ravenously on the leaves before pupating and emerging as a new generation of butterflies. With a wingspan of nearly three inches, the Gulf Fritillary is neither a true fritillary nor a heliconian, but rather is classified as a longwing butterfly. Ranging from New Jersey and Iowa to South America, Gulf Fritillaries are very common throughout the American South.

Where is your passion?

Passion Flower can still be found growing on old homesteads, and seeds and cuttings for rooting are often available free for the asking. Seeds are also available commercially and via heirloom seed exchanges. As catalogues begin arriving in the mail later this fall and winter, be sure to add Passiflora incarnata to your seed order. Neither you nor the butterflies will be disappointed!

Utilized by Native Americans and grown by southern settlers, Passiflora incarnata was introduced in England in 1629 and first offered in an American nursery/seed catalogue in 1811 by the Philadelphia-based Landreth Nursery.

A vigorous grower, the perennial Passiflora climbs by tendrils, reaching 10-20 feet. It can also be grown as a ground cover. Blooming between May and September, Passion Flower produces edible oval fruits old-timers often refer to as maypops. Many a southern kitchen has turned out jars of maypop jelly, and some commercial fruit juices available today contain extract from maypops.

While seeds can be retained from the fruits of Passiflora, it is easily propagated by rooting cuttings.

What's in a name?

Named by Roman Catholic missionaries, according to legend, Passiflora is perhaps best known for its Christian symbolism. Hardly referencing eroticism or sexuality, Passion Flower and its various parts represent Christ's crucifixion. There are ten petals for the ten apostles present at the crucifixion, an ovary column resembling a cross, three stigmas for the nails, colored filaments for the crown of thorns, five pollen-bearing anthers for Christ's wounds and coiling vine tendrils reminiscent of whips or scourges.

A Gracious Southern Host

Passiflora incarnata is especially admired by butterfly lovers because it is a host plant to the Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae). Planted in sufficient quantity along with butterfly-attracting plants like Echinacea, Buddleja and Lantana, Southern gardeners are almost guaranteed to witness nature at work as Gulf Fritillaries are drawn to the garden to lay their eggs on the various parts of Passiflora. The resulting spiny larvae feed ravenously on the leaves before pupating and emerging as a new generation of butterflies. With a wingspan of nearly three inches, the Gulf Fritillary is neither a true fritillary nor a heliconian, but rather is classified as a longwing butterfly. Ranging from New Jersey and Iowa to South America, Gulf Fritillaries are very common throughout the American South.

Where is your passion?

Passion Flower can still be found growing on old homesteads, and seeds and cuttings for rooting are often available free for the asking. Seeds are also available commercially and via heirloom seed exchanges. As catalogues begin arriving in the mail later this fall and winter, be sure to add Passiflora incarnata to your seed order. Neither you nor the butterflies will be disappointed!

From the late 1500s, flowers fell into two groups - passé and fashionable. Passé flowers were both those that were once rare but had become widely available, and those that were found in the gardens of commoners (and so never were of "fashionable" status to begin with). Daffodils fell into both groups, depending on the flower at hand, and these two statuses followed the Narcissus genus across the Atlantic to the British colonies.

While we tend to think everyone had an ornamental flower garden early on in the colonies, such was not the case. It took decades for settlers to become both physically and economically secure enough to start really wasting time and money on ornamental flowers. Even in Merry Olde England, ornamental gardening as its own pursuit didn't really gain traction with the upper classes until the late 1600s. So, although daffodils probably were in someone's garden before 1700, daffodils don't appear in the written record until the early 1700s.

While we tend to think everyone had an ornamental flower garden early on in the colonies, such was not the case. It took decades for settlers to become both physically and economically secure enough to start really wasting time and money on ornamental flowers. Even in Merry Olde England, ornamental gardening as its own pursuit didn't really gain traction with the upper classes until the late 1600s. So, although daffodils probably were in someone's garden before 1700, daffodils don't appear in the written record until the early 1700s.

"But in the time of King Charles IId, Gardening was much improved and became common : I doe beleeve, I may modestly affirm, that there is now ten times as much gardning about London as there was in A° 1660 : and wee have been, since that time, much improved in forreign plants, especially since about 1683, there have been exotick Plants brought into England, no lesse than seven thousand." - John Aubrey, 1691

Ed Harshaw

This intricate Passiflora incarnata bloom was photographed on June 27, 2006 in the garden of Southern Edition editor Greg Freeman by Lowcountry photographer Ed Harshaw. Harshaw's work was featured in the story, Ed Harshaw: Capturing the Splendor of the Lowcountry One Photo at a Time.

In the 1700s, the narcissuses of first rank were tazettas, or polyanthus narcissuses. Esteemed for their showiness and fragrance, tazettas had been brought from as far away as Turkey and the Levant by the Dutch who had begun hybridizing them by the mid-1600s. Next were jonquils, again for their fragrance, followed by the rarer doubles. Uncommon daffodils from the mountains of Portugal were also looked upon favorably. The common double yellow and the single yellow trumpet of English gardens were commoners' flowers in England and so generally commoners' flowers in the colonies.

British botanical texts published in the 1700s help shed light on those daffodils considered "common." Fortunately, botanists habitually mentioned whether a plant was grown in gardens. Another period source is the correspondence between America's great plantsman John Bartram of Germantown (outside Philadelphia) and his fellow Quaker across the Pond in London, Peter Collinson. Ordering lists and diaries of the wealthy, or at least the literate and determined gardener, help round out the picture of daffodils in the British colonies.

How colonists planted their daffodils also followed European conventions. Those of more humble origins laid out basic traditional European farmer gardens - two parallel rows of squares or rectangles. Stretching back to Medieval times, this basic garden pattern can be found from Grumblethorpe of Germantown to coastal North Carolina. Wealthy colonists often followed the dictates of Philip Miller and his many editions of The Gardener.

Colonial gardeners did not have as many individual plants as we do today, and ornamentals were assuredly a luxury. Thus, particularly for Dutch bulbs and other spring ephemerals, each plant or bulb was planted in a rigidly spaced pattern, both for ease of record-keeping as well as management, care and enjoyment. One's "best" bulbs were often also given their own designated raised bed, bordered by boards ("rails") or boxwood, again a continuation of 1600s gardening conventions.

One of Charleston's earliest gardeners, Mrs. Lamboll, luckily had a chatty husband who corresponded with John Bartram. In 1761, Mr. Lamboll remarked upon Mrs. Lamboll's methods:

British botanical texts published in the 1700s help shed light on those daffodils considered "common." Fortunately, botanists habitually mentioned whether a plant was grown in gardens. Another period source is the correspondence between America's great plantsman John Bartram of Germantown (outside Philadelphia) and his fellow Quaker across the Pond in London, Peter Collinson. Ordering lists and diaries of the wealthy, or at least the literate and determined gardener, help round out the picture of daffodils in the British colonies.

How colonists planted their daffodils also followed European conventions. Those of more humble origins laid out basic traditional European farmer gardens - two parallel rows of squares or rectangles. Stretching back to Medieval times, this basic garden pattern can be found from Grumblethorpe of Germantown to coastal North Carolina. Wealthy colonists often followed the dictates of Philip Miller and his many editions of The Gardener.

Colonial gardeners did not have as many individual plants as we do today, and ornamentals were assuredly a luxury. Thus, particularly for Dutch bulbs and other spring ephemerals, each plant or bulb was planted in a rigidly spaced pattern, both for ease of record-keeping as well as management, care and enjoyment. One's "best" bulbs were often also given their own designated raised bed, bordered by boards ("rails") or boxwood, again a continuation of 1600s gardening conventions.

One of Charleston's earliest gardeners, Mrs. Lamboll, luckily had a chatty husband who corresponded with John Bartram. In 1761, Mr. Lamboll remarked upon Mrs. Lamboll's methods:

Ed Harshaw

The manner Mrs. Lamboll manages her Ranunculas & Anemonies every Year, is thus: She prepares Beds of good Rich Mould at least Two Months before she takes up the Flower Roots; that the Earth may be well settled by Rain. Wherever the Ground is low, she raised the Flower Beds, at least half a foot in heighth, and where high flattens them. In Summer time, the leaves of the Flower Roots being thoroughly dry, immediately after a Shower of Rain happens, she takes up the said Roots, divides & cleanses them (but not by washing) from Insects, then makes slight holes with the Fingers on the Tops of the prepared Beds, places the Roots about four inches asunder and covers them over with Dirt, Scrap'd from the paths, about half an Inch deep; strewing it over with the Fingers. And if the Rain fails she afterwards causes the Beds of the Flower Roots to be Watered gently, such Water having first stood a Convenient time in the Sun. In Cold Weather she causes the Flower Beds to be Cover'd and Shelter'd; especially when they have begun to Sprout.

As gardening rose in importance to wealthy colonists, so too did their need for trained help. Originally often indentured servants, later a few of these gardeners went into business for themselves as nurserymen. Henry Laurens, a man of considerable stature in Charleston, employed such a gardener - who in turn established his own nursery. On a trip through South Carolina in 1765, John Bartram visited the noted garden of Laurens at his plantation, noting the contents of the garden and its overall dimensions, but nothing of its internal pattern. A brick walled affair, it measured 200 yards by 150 yards and boasted fruit, olive, caper and lime trees. Fortuituously, some of Laurens' plant orders reside tucked away in his personal papers. In 1763 he ordered from Sarah Nicholson and Company in England "Pseudo Narcissus or Yellow (or white) Daffodil" along with martagon lily, double nasturtium, ranunculus, peony and anemone. Thus it is interesting that a man of stature such as Henry Laurens wrote to order the commoner's N. pseudonarcissus or a yellow and white daffodil. Laurens' British gardener, John Watson, who set up his own nursery business, imported and sold Dutch bulbs. His advertisement for 1765 included fashionable double jonquils along with the hyacinths, tulips, lilies, anemones and ranunculus.

The Federal period (1789 to 1820) was a golden age of sorts for daffodils in American gardens. The varieties ordered became esoteric, but the preference for doubles and jonquils remained. The plants order list of South Carolina governor and avid horticulturalist Henry Middleton (1770-1841), dating to the early 1800s, reflects this broadening of the daffodil palate, while sticking to those forms suitable for a garden of distinction, namely doubles as well as Narcissus poeticus and Narcissus minor. Presumably these were planted in the formal parterre beds at Middleton Place.

In the antebellum period (1820-1860), daffodils fell to a "filler" status in high-fashion gardens. The more esoteric daffodils of the Federal era fell away, but those tough and dependable varieties carried on in many gardens. The preference for showy doubles, fragrant jonquils and Dutch florist tazettas remained.

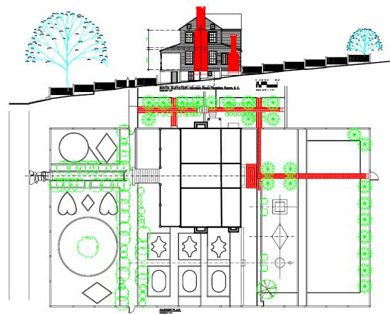

Many Southerners held on to the formal parterre gardens, the geometric patterns of yore suiting the tradition-conscious region. One such antebellum garden in South Carolina is at Mountain Shoals Plantation in Spartanburg County. Constructed around 1840 by first-generation Irish families, the fieldstone-lined beds are in keeping with the Piedmont garden tradition. But the parterre bed patterns, instead of showing English design influences, apparently are of Irish folklore iconography instead. A garden of love for newlyweds, the Eternity circle is flanked by two hearts (for the couple) and a diamond for prosperity.

After the Civil War, across America rose a number of new landscaping trends, two of which were particularly important for daffodils. One was the rise of "the old-fashioned garden," a re-invention of colonial and antebellum gardens romancing a period of stability before the onslaught of the Industrial Revolution and mass immigration. The second was the "Wild Garden" philosophy from Britain championed by William Robinson - who, conveniently, was friends with the daffodil's biggest champion Peter Barr.

As Peter Barr introduced the first true hybrid daffodils with new forms and new colors, William Robinson gave them a new home outside the stuffy rigid parterre - the sweeping drift along walkways, lawns, water features and the like. By the late 1800s to early 1900s, gardeners of even modest means were planting garish beds of tulips and hyacinths in bull's eye patterns in the middle of their lawns, but scatter-planting daffodils along their woodlands.

The Federal period (1789 to 1820) was a golden age of sorts for daffodils in American gardens. The varieties ordered became esoteric, but the preference for doubles and jonquils remained. The plants order list of South Carolina governor and avid horticulturalist Henry Middleton (1770-1841), dating to the early 1800s, reflects this broadening of the daffodil palate, while sticking to those forms suitable for a garden of distinction, namely doubles as well as Narcissus poeticus and Narcissus minor. Presumably these were planted in the formal parterre beds at Middleton Place.

In the antebellum period (1820-1860), daffodils fell to a "filler" status in high-fashion gardens. The more esoteric daffodils of the Federal era fell away, but those tough and dependable varieties carried on in many gardens. The preference for showy doubles, fragrant jonquils and Dutch florist tazettas remained.

Many Southerners held on to the formal parterre gardens, the geometric patterns of yore suiting the tradition-conscious region. One such antebellum garden in South Carolina is at Mountain Shoals Plantation in Spartanburg County. Constructed around 1840 by first-generation Irish families, the fieldstone-lined beds are in keeping with the Piedmont garden tradition. But the parterre bed patterns, instead of showing English design influences, apparently are of Irish folklore iconography instead. A garden of love for newlyweds, the Eternity circle is flanked by two hearts (for the couple) and a diamond for prosperity.

After the Civil War, across America rose a number of new landscaping trends, two of which were particularly important for daffodils. One was the rise of "the old-fashioned garden," a re-invention of colonial and antebellum gardens romancing a period of stability before the onslaught of the Industrial Revolution and mass immigration. The second was the "Wild Garden" philosophy from Britain championed by William Robinson - who, conveniently, was friends with the daffodil's biggest champion Peter Barr.

As Peter Barr introduced the first true hybrid daffodils with new forms and new colors, William Robinson gave them a new home outside the stuffy rigid parterre - the sweeping drift along walkways, lawns, water features and the like. By the late 1800s to early 1900s, gardeners of even modest means were planting garish beds of tulips and hyacinths in bull's eye patterns in the middle of their lawns, but scatter-planting daffodils along their woodlands.

A Gulf Fritillary butterfly paying a visit to Lantana 'Miss Huff'

Larvae of the Gulf Fritillary butterfly feeding on the leaves of Passiflora incarnata

This botanical print by renowned English naturalist and illustrator James Sowerby depicts Narcissus pseudonarcissus, a commoner's flower in the 1700s. These daffodils are found in abundance on old homesteads throughout the American South today.

Narcissus 'Albus Plenus Odorata' or Narcissus poeticus 'Plenus' - formerly known as N. poeticus 'Flore Pleno', as illustrated by F. W. Burbridge in this 1875 print - is a double form of Narcissus poeticus, the "poet's daffodil."

Martin Meek

Mountain Shoals Plantation, Enoree, South Carolina

Note the Eternity circle flanked by two hearts (for the couple) and a diamond for prosperity.

Note the Eternity circle flanked by two hearts (for the couple) and a diamond for prosperity.

Daffodils in the old-fashioned garden took a different turn. Easily considered "grandmother's" plants, most gardeners tucked the bulbs in as background plants in the mixed border. Some, however, got busy with their bulbs - adding them to antebellum boxwood parterres or even creating new gardens of the old familiar forms of their childhoods, but using bulbs (primarily daffodils) instead of boxwood or fieldstones. Many an old antebellum parterre got a sprucing up in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with bulbs - yellow and white daffodils, red spider lilies, light blue Ipheion (star flowers), dark blue Roman hyacinths, Spanish bluebells and white snowflakes, with a dose of red spider lilies for the late summer/early fall. Other spring and summer bulbs were probably added, but these are the tough ones still surviving one hundred years later. The antebellum boxwood parterre of the Shillito-Townsend house in Abbeville is one such example.

A fascinating example of a new bulb garden in the old design style is that found at The Oaks near Columbia. A photograph of the Lemmon family dating to around 1870 shows the extended family in the yard in front of the plantation house. Interestingly, wires have been strung over the front porches for vines to grow up in a three-tiered diamond pattern. In the backyard, some time probably in the early twentieth century, it appears the young daughters in that photograph created a geometric garden in bulbs using daffodils, jonquils, paperwhites, hyacinths and red spider lilies. In the back of the expansive circle and square affair is a running diamond pattern just like the old photograph - but double planted with jonquils and red spider lilies, providing gold diamonds in the spring and red diamonds in the fall.

Both Mountain Shoals and The Oaks were featured gardens on the 2011 Follow the Blooms Tour, hosted by the South Carolina Garden Club, Inc. Granted, the tour dates were after the spring bulb season, but these tours are a wonderful way to see South Carolina's gardening heritage. The 2012 Tour runs from March 24 to April 20, 2012.

A fascinating example of a new bulb garden in the old design style is that found at The Oaks near Columbia. A photograph of the Lemmon family dating to around 1870 shows the extended family in the yard in front of the plantation house. Interestingly, wires have been strung over the front porches for vines to grow up in a three-tiered diamond pattern. In the backyard, some time probably in the early twentieth century, it appears the young daughters in that photograph created a geometric garden in bulbs using daffodils, jonquils, paperwhites, hyacinths and red spider lilies. In the back of the expansive circle and square affair is a running diamond pattern just like the old photograph - but double planted with jonquils and red spider lilies, providing gold diamonds in the spring and red diamonds in the fall.

Both Mountain Shoals and The Oaks were featured gardens on the 2011 Follow the Blooms Tour, hosted by the South Carolina Garden Club, Inc. Granted, the tour dates were after the spring bulb season, but these tours are a wonderful way to see South Carolina's gardening heritage. The 2012 Tour runs from March 24 to April 20, 2012.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734 - 1777 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992).

James R. Cothran, Gardens and Historic Plants of the Antebellum South (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003).

William Robinson, The Wild Garden (London: John Murray, 1870, 1881, 1903).

RECOMMENDED READING

Alan W. Armstrong (ed.), "Forget Not Mee & My Garden...," Selected Letters 1725 - 1768 of Peter Collinson F.R.S. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002).

Barbara Sarudy, Gardens and Gardening in the Chesapeake, 1700-1805 (Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).

William C. Welch and Greg Grant, The Southern Heirloom Garden (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 1995).

Andrea Wulf, The Brother Gardeners: Botany, Empire and the Birth of an Obsession (New York: Vintage Books, 2008).

The Magnolia (published by Southern Garden History Society), back issues and plants list.

Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734 - 1777 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992).

James R. Cothran, Gardens and Historic Plants of the Antebellum South (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003).

William Robinson, The Wild Garden (London: John Murray, 1870, 1881, 1903).

RECOMMENDED READING

Alan W. Armstrong (ed.), "Forget Not Mee & My Garden...," Selected Letters 1725 - 1768 of Peter Collinson F.R.S. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002).

Barbara Sarudy, Gardens and Gardening in the Chesapeake, 1700-1805 (Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).

William C. Welch and Greg Grant, The Southern Heirloom Garden (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 1995).

Andrea Wulf, The Brother Gardeners: Botany, Empire and the Birth of an Obsession (New York: Vintage Books, 2008).

The Magnolia (published by Southern Garden History Society), back issues and plants list.

Author: Sara Van Beck. Published March 27, 2012.

Copyright

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

All materials contained on this site, including text and images, are protected by copyright laws and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. Where applicable, use of some items contained on this site may require permission from other copyright owners.

Fair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.

Contact Greg Freeman or SouthernEdition.comFair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.