Southern Exposure

Dinkler Hotels

Bastions of Excellence Set Southern Hotelier Apart

Bastions of Excellence Set Southern Hotelier Apart

When one thinks of fine, old southern hotels, certainly Memphis' Peabody, Atlanta's Georgian Terrace or Asheville's Grove Park Inn must come to mind. However, many other renowned properties, characterized by warm hospitality, luxurious accommodations and unparalleled service, existed in the first half of the twentieth century, and many of these were owned or managed by Atlanta-based Dinkler Hotel Corporation.

The First Dinkler Hotel

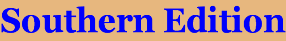

Louis Jacob Dinkler was born in Nashville in the 1860s, the son of Jacob (an immigrant from the Bavarian region of Germany) and Josephine Dinkler. Initially a confectioner (baker) like his father, L. J. Dinkler later entered the hotel business, opening the Hotel Dinkler in Macon, Georgia in July 1911. L. J. Dinkler's great-grandson, Carling Dinkler III, president of Custom Conventions (a destination management company with offices in New Orleans and Las Vegas) relates that it was from this initial establishment that the Dinkler hotel dynasty was born. As the elder Dinkler successfully grasped the art of innkeeping in Macon, it is unclear whether he aspired to own an entire chain. Nonetheless, the family amassed many hotels, and the Dinkler name became widely recognized and well-respected in the hospitality industry. Due to the enthusiasm and entrepreneurial spirit of two subsequent generations, Dinkler Hotels was vibrant for the better part of a century, well after the opening of L. J. Dinkler's original hotel in Macon.

Louis Jacob Dinkler was born in Nashville in the 1860s, the son of Jacob (an immigrant from the Bavarian region of Germany) and Josephine Dinkler. Initially a confectioner (baker) like his father, L. J. Dinkler later entered the hotel business, opening the Hotel Dinkler in Macon, Georgia in July 1911. L. J. Dinkler's great-grandson, Carling Dinkler III, president of Custom Conventions (a destination management company with offices in New Orleans and Las Vegas) relates that it was from this initial establishment that the Dinkler hotel dynasty was born. As the elder Dinkler successfully grasped the art of innkeeping in Macon, it is unclear whether he aspired to own an entire chain. Nonetheless, the family amassed many hotels, and the Dinkler name became widely recognized and well-respected in the hospitality industry. Due to the enthusiasm and entrepreneurial spirit of two subsequent generations, Dinkler Hotels was vibrant for the better part of a century, well after the opening of L. J. Dinkler's original hotel in Macon.

This postcard (with a 1914 postmark) depicts L. J. Dinkler's first hotel---the Hotel Dinkler in Macon, Georgia.

A Family Affair

Honing his business acumen from which he would later benefit, L. J. Dinkler remained in Macon for several years before eventually settling in Atlanta. There, the family business expanded with the purchase of downtown's Kimball House Hotel.

Honing his business acumen from which he would later benefit, L. J. Dinkler remained in Macon for several years before eventually settling in Atlanta. There, the family business expanded with the purchase of downtown's Kimball House Hotel.

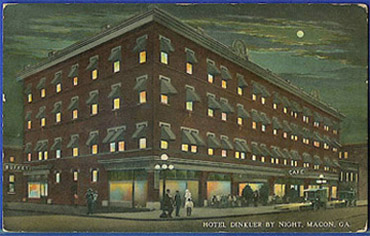

This old advertising card features seven of Dinkler's most notable hotels. The chain, at one point or another, also included the Kentucky Hotel in Louisville and the Lookout Mountain Hotel high above Chattanooga as well as properties in Jacksonville and Myrtle Beach.

Upon graduating from Spring Hill College in Alabama, Dinkler's son, Carling, joined him in running the company. In fact, it was Carling who successfully facilitated the purchase of Hotel Ansley (prominently located at Atlanta's Forsyth and Williams Streets). By the stock market crash of 1929, the Dinklers owned or managed some 22 hotels throughout the southeastern United States, Dinkler III recollects.

L. J. Dinkler, 67, committed suicide with a pistol in December 1928 in the subbasement of the Piedmont Hotel, a property the Dinklers had leased just five years earlier in a newsworthy deal totalling several hundred thousand dollars. The Atlanta Constitution reported "despondency over ill health" as Dinkler's reason for ending his life.

Born on August 4, 1919 at the Kimball House, Carling Dinkler Jr. would follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. Formally educated at the University of Georgia and Loyola University in New Orleans, Dinkler Jr. became vice president of Dinkler Hotels, and was reportedly the youngest hotel executive in the nation. An effective leader and savvy businessman, Dinkler Jr. transformed the company into one of the most formidable hospitality chains of its day.

L. J. Dinkler, 67, committed suicide with a pistol in December 1928 in the subbasement of the Piedmont Hotel, a property the Dinklers had leased just five years earlier in a newsworthy deal totalling several hundred thousand dollars. The Atlanta Constitution reported "despondency over ill health" as Dinkler's reason for ending his life.

Born on August 4, 1919 at the Kimball House, Carling Dinkler Jr. would follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. Formally educated at the University of Georgia and Loyola University in New Orleans, Dinkler Jr. became vice president of Dinkler Hotels, and was reportedly the youngest hotel executive in the nation. An effective leader and savvy businessman, Dinkler Jr. transformed the company into one of the most formidable hospitality chains of its day.

The Dinkler Tradition

Continually striving to ensure customer satisfaction and stimulate repeat business, the Dinklers were pioneers and trendsetters in their field. "The Dinkler tradition has [always] been service and quality," says Dinkler III. Hotel employees "used to wear badges that said Courtesy is Contagious," he adds. Dinkler is convinced that many of today's hoteliers are simply "too busy with their 'heads on beds quotas'."

Leaders in the convention industry, Dinkler Hotels especially played a significant role in solidifying a number of southern cities as convention destinations. Always innovative, Dinkler was one of the first companies to develop an in-house "credit card," a move that provided convenience for both business and leisurely travelers. Customers were given a metal tag (complete with a personal identification number) that attached to a key chain. Upon checking into a Dinkler hotel, guests simply displayed their key chain tag and were billed directly, says Dinkler III.

The Dinkler family of hotels not only included big city locations catering to the convention-going businessman, but the company was even diversified with properties appealing to affluent tourists in locales like Myrtle Beach and Chattanooga.

For the reading pleasure of its guests, Dinkler Hotels published Inn Dixie, a monthly magazine that featured articles about current events, celebrities and convention-oriented news. Printed by Atlanta-based Higgins-McArthur Company, the publication was a great promotional tool for the hotel chain.

Additionally, other hotels viewed food service as a necessary evil and often unprofitable endeavor, but Dinkler III says his father "was very interested in the food and beverage side of the industry," and was the first hotelier to join the American Restaurant Association. Dinkler Jr. proved that he could turn a profit by owning his own restaurants rather than leasing space to restauranteurs. "My father really believed that he could make profit centers in his hotels," Dinkler III says. And he did.

Tragedy Strikes the Dinkler Family Again

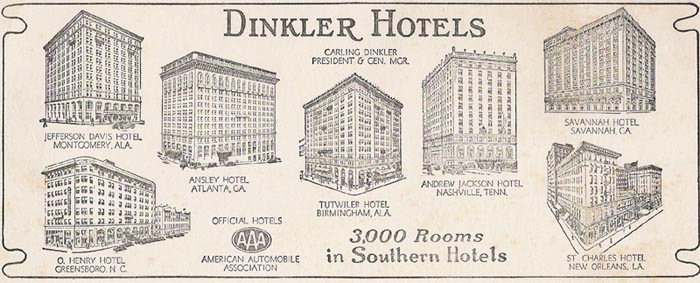

On January 30, 1961, 66-year-old Carling Dinkler Sr., then-president of Dinkler Hotels, plunged twelve stories to his death from his personal suite at the Dinkler Plaza Hotel (formerly Hotel Ansley) in Atlanta. Fulton County Medical Examiner Dr. Tom Dillon determined the death "was caused from injuries received in a suicidal jump." No note was found.

Dinkler Sr. had been ill and depressed following intestinal surgery he had undergone eight months earlier, and Dinkler Jr. told Atlanta police that his father had endured "considerable pain of late" and feared a relapse of his sickness. In response to inquiries from the press, a spokesman acknowledged the family was "puzzled" because Dinkler Sr. had been in good spirits the night before. While the events leading to his death appeared to be quite clear, some felt that such a public act of suicide was the last thing to be expected of someone as private and reserved as Dinkler Sr. (whose modest and unassuming nature was evidenced by the fact that he had a chauffeur, but rode in a Chevrolet).

The abrupt death of its president came at a time when Dinkler Hotels was planning to merge with New York-based Associated Hotels Corporation. Dinkler holdings included the Dinkler Plaza, the Tutwiler and the Andrew Jackson hotels as well as the Dinkler-Belvedere Motor Inn and the Belvedere Ice Rink in Decatur, Georgia. Interestingly, Dinkler Sr. owned a hobby farm in Decatur, an Atlanta suburb just minutes from Emory University, and his ice rink was reportedly the first to be constructed in the entire metropolitan Atlanta area.

Upon his father's death, Carling Dinkler Jr. became president of Dinkler Hotels.

New York Syndicate Buys Dinkler Hotels

With the Associated Hotels Corporation merger falling through, Transcontinental Investing Corporation, just weeks following the death of Carling Dinkler Sr., purchased from Dinklers the Dinkler Plaza, the Tutwiler, the Andrew Jackson, the Dinkler-Belvedere Motor Inn and the Shaw Park Beach Club in Ochos Rios, Jamaica, for $15 million. Under a long-term contract, Carling Dinkler Jr. remained president and general manager of the five properties for the New York syndicate of real estate investors. Dinkler Jr. also became a member of Transcontinental's board of directors.

Continually striving to ensure customer satisfaction and stimulate repeat business, the Dinklers were pioneers and trendsetters in their field. "The Dinkler tradition has [always] been service and quality," says Dinkler III. Hotel employees "used to wear badges that said Courtesy is Contagious," he adds. Dinkler is convinced that many of today's hoteliers are simply "too busy with their 'heads on beds quotas'."

Leaders in the convention industry, Dinkler Hotels especially played a significant role in solidifying a number of southern cities as convention destinations. Always innovative, Dinkler was one of the first companies to develop an in-house "credit card," a move that provided convenience for both business and leisurely travelers. Customers were given a metal tag (complete with a personal identification number) that attached to a key chain. Upon checking into a Dinkler hotel, guests simply displayed their key chain tag and were billed directly, says Dinkler III.

The Dinkler family of hotels not only included big city locations catering to the convention-going businessman, but the company was even diversified with properties appealing to affluent tourists in locales like Myrtle Beach and Chattanooga.

For the reading pleasure of its guests, Dinkler Hotels published Inn Dixie, a monthly magazine that featured articles about current events, celebrities and convention-oriented news. Printed by Atlanta-based Higgins-McArthur Company, the publication was a great promotional tool for the hotel chain.

Additionally, other hotels viewed food service as a necessary evil and often unprofitable endeavor, but Dinkler III says his father "was very interested in the food and beverage side of the industry," and was the first hotelier to join the American Restaurant Association. Dinkler Jr. proved that he could turn a profit by owning his own restaurants rather than leasing space to restauranteurs. "My father really believed that he could make profit centers in his hotels," Dinkler III says. And he did.

Tragedy Strikes the Dinkler Family Again

On January 30, 1961, 66-year-old Carling Dinkler Sr., then-president of Dinkler Hotels, plunged twelve stories to his death from his personal suite at the Dinkler Plaza Hotel (formerly Hotel Ansley) in Atlanta. Fulton County Medical Examiner Dr. Tom Dillon determined the death "was caused from injuries received in a suicidal jump." No note was found.

Dinkler Sr. had been ill and depressed following intestinal surgery he had undergone eight months earlier, and Dinkler Jr. told Atlanta police that his father had endured "considerable pain of late" and feared a relapse of his sickness. In response to inquiries from the press, a spokesman acknowledged the family was "puzzled" because Dinkler Sr. had been in good spirits the night before. While the events leading to his death appeared to be quite clear, some felt that such a public act of suicide was the last thing to be expected of someone as private and reserved as Dinkler Sr. (whose modest and unassuming nature was evidenced by the fact that he had a chauffeur, but rode in a Chevrolet).

The abrupt death of its president came at a time when Dinkler Hotels was planning to merge with New York-based Associated Hotels Corporation. Dinkler holdings included the Dinkler Plaza, the Tutwiler and the Andrew Jackson hotels as well as the Dinkler-Belvedere Motor Inn and the Belvedere Ice Rink in Decatur, Georgia. Interestingly, Dinkler Sr. owned a hobby farm in Decatur, an Atlanta suburb just minutes from Emory University, and his ice rink was reportedly the first to be constructed in the entire metropolitan Atlanta area.

Upon his father's death, Carling Dinkler Jr. became president of Dinkler Hotels.

New York Syndicate Buys Dinkler Hotels

With the Associated Hotels Corporation merger falling through, Transcontinental Investing Corporation, just weeks following the death of Carling Dinkler Sr., purchased from Dinklers the Dinkler Plaza, the Tutwiler, the Andrew Jackson, the Dinkler-Belvedere Motor Inn and the Shaw Park Beach Club in Ochos Rios, Jamaica, for $15 million. Under a long-term contract, Carling Dinkler Jr. remained president and general manager of the five properties for the New York syndicate of real estate investors. Dinkler Jr. also became a member of Transcontinental's board of directors.

Hotel Ansley, built by Edwin P. Ansley of Ansley Park fame, was the second downtown Atlanta hotel purchase for Dinkler Hotels, and it was here that the Dinkler corporate office was based. Renamed the Dinkler Plaza Hotel in 1953 (40 years after its construction), the city presented civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with an historic congratulatory banquet, Atlanta's first biracial formal dinner, in the hotel's magnificent chandeliered ballroom upon his receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Originally a project of the Applebrook Hotel Company, Dinkler Hotels acquired this Jacksonville landmark, naming it the Carling Hotel. Designed by the architectural firm of Thompson, Holmes & Converse and completed in 1926, the 13-story structure became the Roosevelt Hotel in 1936. Site of a tragic fire that killed 22 guests in 1963, the property is now Carlington Apartments.

Touted as the "Castle in the Clouds," the Lookout Mountain Hotel was built in 1928 for almost $1.5 million. With 200 rooms offering incredible views of Lookout Valley, the property, once a popular tourist destination, is now Covenant College.

The October 1942 issue of Inn Dixie prominently featured the Ansley, Savannah, O. Henry, St. Charles, Andrew Jackson, Tutwiler and Jefferson Davis hotels. Indicative of the times, there was much emphasis throughout the issue on winning the war [World War II], and numerous ads urged readers to buy war bonds. One article even points out that an unprecedented million-dollar War Bond luncheon, attended by "such radio and screen stars as Vera Zorina, Andy Devine and Laraine Day..." was held at the Tutwiler in Birmingham. Other articles included "Fashions in Dixie: War Influence on Winter Clothes" and "Myths, Legends and Mysteries of the Southeast." Miscellaneous photos included one of a young Carling Dinkler Jr. and his friend, Sgt. Charles Hopkins, Jr., showing off a nice stringer of fish they had caught "twenty minutes from Five Points," and a shot of Jack Coffey whose "Rockin' Rhythm" orchestra was playing the Ansley Hotel Rainbow Roof, a venue billed as "The South's Smartest Supper Club." A popular nightspot for locals and hotel guests seeking entertainment and fine food in "air-conditioned comfort," the Rainbow Roof offered "Delicious Six-Course Dinners from $1.50" with no admission or cover charges. Advertisers in this issue of Inn Dixie promoted everything from laundry services to cigars to fresh flowers. Worth noting, Ivan Allen-Marshall Company of Atlanta, founded by Ivan Allen, Sr., advertised its line of office equipment, printers and lithographers. (Ivan Allen Jr. would become one of Atlanta's most famous mayors.) And Spring Hill College, the Alabama school where Carling Dinkler Sr. received his education, placed a small ad, which Carling Dinkler III says was likely published free of charge.

Dinkler Plaza Hotel Becomes Battleground in Civil Rights Struggle

During a tumultuous era, in which racial segregation was the norm and the fight for civil rights would turn ugly, Dinkler Hotels became one of the first hospitality companies to integrate, but change came neither quickly nor easily. Referring to the unwavering attitudes of the day, Inman Allen, son of the late Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr., acknowledges, "We were a segregated society in the 50s and up into the 60s." And, though the widespread violence observed in cities like Selma and Montgomery was kept at a minimum in Atlanta, many white business owners were very reluctant to accept and implement progressive reforms.

Despite a change in ownership, the Dinklers, under the auspices of a management contract, remained the primary policy makers for the hotels. While the Dinkler family was by no means a clan of bigots, their perspective on segregation was more reflective of the times and accepted business practices than personal convictions. The Dinklers ultimately yielded to the call for integration, but some prominent Atlantans like eventual Georgia governor Lester Maddox (who opted to close his Pickrick Cafeteria, an Atlanta institution, rather than serve black customers) stubbornly refused to relinquish their Jim Crow persuasions.

That said, between 1961 and 1964, the Dinkler Plaza Hotel was the focus of several protests and racial controversies, some of which made national headlines.

During a tumultuous era, in which racial segregation was the norm and the fight for civil rights would turn ugly, Dinkler Hotels became one of the first hospitality companies to integrate, but change came neither quickly nor easily. Referring to the unwavering attitudes of the day, Inman Allen, son of the late Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr., acknowledges, "We were a segregated society in the 50s and up into the 60s." And, though the widespread violence observed in cities like Selma and Montgomery was kept at a minimum in Atlanta, many white business owners were very reluctant to accept and implement progressive reforms.

Despite a change in ownership, the Dinklers, under the auspices of a management contract, remained the primary policy makers for the hotels. While the Dinkler family was by no means a clan of bigots, their perspective on segregation was more reflective of the times and accepted business practices than personal convictions. The Dinklers ultimately yielded to the call for integration, but some prominent Atlantans like eventual Georgia governor Lester Maddox (who opted to close his Pickrick Cafeteria, an Atlanta institution, rather than serve black customers) stubbornly refused to relinquish their Jim Crow persuasions.

That said, between 1961 and 1964, the Dinkler Plaza Hotel was the focus of several protests and racial controversies, some of which made national headlines.

This unmailed post card depicting the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans is obviously very old even though no postmark is present to provide a more accurate indication of its age. Note the horse-drawn carriages, Model T automobiles and street cars. At the time this card was published, the St. Charles was the property of Alfred S. Amer & Company, Ltd. The Dinklers later managed this hotel, eventually acquiring it in 1958. An article, appearing in The New York Times the following year, announced Dinkler Hotels' sale of the 500-room New Orleans landmark to the Sheraton Corporation of America for $5 million, making it Sheraton's 53rd hotel.

One notable example was the national convention of the Junior Chambers of Commerce which was held June 19-22, 1961 at the Dinkler Plaza. While African Americans were generally able to attend meetings and conferences at all-white hotels in Atlanta, these hotels offered no dining or lodging options to black convention goers. Therefore, United Press International's coverage of the convention, insisting that the Dinkler Plaza was housing Pennsylvania Jaycees president William D. Johnson, a black man, stirred much controversy and prompted an earnest public relations effort by hotel management. The Associated Press further reported that Johnson had been "assigned" to the Dinkler Plaza. In response, E. M. Turlington, vice president of the Dinkler Hotel Corporation told the Atlanta Constitution, "Reports that Negro delegates have been registered either under their own name or fictitious names at the Dinkler Plaza Hotel are completely erroneous."

However, some 45 years later, Dick Thomas, former Director of Sales for Dinkler Hotels, recounts what he calls "the toughest day I ever had in my life." And his memory of what took place behind closed doors contrasts sharply with the Dinkler Plaza's public assertions. Serving as the Jaycees' national public relations chairman, Thomas recalls the protests and bomb threats that ensued when the news circulated that William D. Johnson "had a suite at the hotel." Even some hotel employees were irate, Thomas says. Shocked that Atlanta, once declared to be the "city too busy to hate," was still experiencing such racial strife in spite of changing views and recent advances, Thomas says the hotel essentially bowed to pressure. To ensure his safety and appease the dissenters, a limousine was summoned, and Johnson (who, as rumored, did have a room at the Dinkler Plaza) was discreetly taken to a black-owned hotel.

Months later, in October 1961, the Dinkler Plaza was the site of a national meeting of Employment Security Program administrators. Citing the hotel's racial policies, 22 states boycotted the event. Marion Williamson, Georgia's Employment Security director, called the racial issue "artificial," but the hotel was once again cast in a negative light, both locally and nationally.

More bad press came in November 1961 when U. S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara traveled to Atlanta to address a segregated audience at the Dinkler Plaza. The New York Times covered McNamara's every move from his arrival at the airport to his cab ride to the hotel. At the last minute, Delta Airlines "diverted the huge Boeing 707 from its designated gate" apparently because of the "presence of Negro demonstrators," the newspaper reported. As McNamara made his way up the concourse, Times reporter Claude Sitton inquired what he thought of the protest, but McNamara denied being aware of the demonstration. Asked to turn his head toward the protesters, McNamara did so and then arrogantly refused to admit he had seen anyone!

A taxi transported McNamara from the airport to a side entrance of the Dinkler Plaza. As he spoke at the dinner honoring U. S. Senator Richard B. Russell and U. S. Representative Carl Vinson, picketers representing the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) protested outside. Holding signs that read "Negroes in the Peace Corps but not the Dinkler" and "Mr. Secretary, you attend this dinner at the expense of human dignity," neither the protesters nor their cause was acknowledged in McNamara's speech. Having attended the event with President John F. Kennedy's apparent blessing, there was much concern within the African American community. After all, blacks had generally supported the Kennedy Administration, but even civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. pondered if Kennedy had "merited the overwhelming support received from Negroes in the last Presidential election."

In March 1962, the NAACP announced plans to hold its annual meeting in Atlanta in July. Expected to draw 1500 to 2000 delegates, the civil rights group vowed to hold the convention regardless of whether Atlanta hotels would accommodate black guests. News of the meeting prompted discussion among members of the Atlanta Hotel Association, and the Dinkler Plaza's own A. J. Crocy (who was also president of the AHA) publicly stated, "Any action taken will come only after long, conscientious deliberations . . . " In the end, the AHA was unrelenting.

"At Your Service"

Like many other southern hoteliers, Dinkler Hotels continued to refuse black guests into the early 1960s, but the company had no qualms about employing African Americans in service positions.

"Maynard Jackson was [once] a waiter at the Dinkler Plaza," Dinkler III recalls, referring to the future Atlanta mayor. In fact, Calvin H. Gibson Sr. (1892-1988), a 60-year employee of Dinkler Hotels and headwaiter for the Dinkler Plaza, hired numerous black college students, including Jackson. "Providing them with jobs that helped pay for their expenses," according to his obituary in the May 19, 1988 Atlanta Constitution, Gibson was noted for his integrity, character and positive effect on young, impressionable students. Crediting Gibson's impact on his life and career, Mayor Jackson said, "He taught me how to wait tables and keep my nose clean, emphasized fine character, clean personal appearance and hard work."

While a student at Clark College, African American Marvin Arrington worked at the Dinkler Plaza under Gibson to earn part of his tuition. An eventual president of the Atlanta City Council, Arrington told the Constitution, "It gave me good work ethics, and he [Gibson] was a part of that growth."

The Turning Point

Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. (1911-2003), a Dinkler family friend, was "credited with leading the city through an era of significant and economic growth" and was "able to broker more peaceful paths to integration," Tammy H. Galloway wrote for the New Georgia Encyclopedia. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution described him as having a "buoyant personality, progressive political style and aristocratic demeanor," and recognized Allen for "bringing major league sports to the South." Undoubtedly, it would take a leader of Allen's stature and charisma to sway hard-line segregationists, and hindsight reveals that his persistence prevailed.

Even though many Atlanta businesses, at Allen's urging, opened their doors to African Americans well before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Dinkler III remembers the adminstration of President Kennedy playing a role in motivating his family to amend its policies regarding the acceptance of black customers.

"Bobby Kennedy called and said, 'Carling, the president would really appreciate it if you would integrate your hotels,' " Dinkler III says. That evening, Dinkler Jr. arrived home from the office and gathered his family together for a meeting. Explaining that the Attorney General had telephoned him about the matter, the family agreed that complying with Kennedy's request would be the right thing to do. "It's gonna cost us money," the elder Dinkler conceded, but Dinkler III says, "We did it anyway."

On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas and, on January 11, 1964, fourteen major Atlanta hotels (including the Dinkler Plaza) announced from Mayor Allen's office their pledge to accept reservations regardless of race (although several had already been quietly accepting black guests).

As Dinkler had predicted, the decision was not without repercussions. Several conventions canceled their reservations, and Dinkler III says a bomb was even placed in the mailbox of the Dinkler family home in Atlanta. Nonetheless, Dinkler Hotels set a positive example, and the family never regretted its decision.

Dinkler Plaza Hotel Site of Historic Banquet

An extraordinary orator and brilliant leader, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. unequivocally impacted the civil rights movement, persevering with organized peaceful protests, in spite of persecutions and numerous setbacks. Violent retaliations against King-led marches attracted attention both nationally and internationally, ultimately drawing sympathy and recruiting allies for the cause. As a result of his tireless labor and advocacy of non-violent demonstration, Dr. King received the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Dr. King, who had been treated like royalty in Oslo upon receiving the Nobel Prize, returned to Atlanta where enthusiasm was lukewarm at best. Initially, ticket sales for a monumental integrated banquet city leaders were holding at the Dinkler Plaza to honor King were fickle, but Coca Cola Company chairman and CEO J. Paul Austin reportedly fostered support and created anticipation for the dinner and, thanks to his bold stand, the banquet tickets were much sought after and sold out quickly.

"More than 1,500 people---the cream of Atlanta's business, civic, political and religious communities---jammed the Dinkler Plaza Hotel downtown for the three-hour affair. Outside, police were on hand to control picketing that never materialized," the Journal-Constitution stated in a 2002 article, reflecting on the January 29, 1964 event.

Reminiscing of the evening, Mayor Ivan Allen Jr., in his book Mayor: Notes on the Sixties (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971.) wrote, "Somebody came up to the Reverend Sam Williams and me and apologized to us that the dinner was going to run about forty-five minutes late because of the unexpectedly large turnout. 'Don't worry about that,' I said. 'My friend Sam Williams has been waiting for a hundred years to get in that ballroom, and forty-five minutes one way or the other isn't going to bother him much.' "

Janice Rothschild Blumberg, widow of Rabbi Jacob Rothschild, described the unforgettable evening in an interview with the Constitution. "At the end, everyone spontaneously joined hands and sang 'We Shall Overcome.' If there were any dry eyes, I didn't see them."

Other Memorable Moments at the Dinkler Plaza

Presidential stays immediately come to mind for Carling Dinkler III when asked which guests he remembers most. According to Dinkler, both Presidents Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson stayed at the Dinkler Plaza. A teenage boy at the time, he especially recalls the occasions because three floors were always rented. For security reasons, the president and his entourage would have one level to themselves, and the immediate floors below and above were off limits to other hotel guests.

James F. "Jimmy" Campbell worked for 35 years as manager of the hotel's bellboy staff. When he died in 2005, at the age of 94, family and friends reminisced of Campbell's days at the Dinkler Plaza. Campbell shook hands with everyone from presidents to celebrities like Bing Crosby. A daughter, Mary Anderson, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, "He met Elvis and got his autograph for me when I was a teenager, and I thought I'd died and gone to heaven." The newspaper reported that Campbell was always eager to share a story about his experiences at the Dinkler Plaza and, from the sound of it, he had quite a few to tell.

The Dinklers Dock in Miami . . . Literally!

Following the sale of the Dinkler hotels and his eventual departure from managing the properties, Carling Dinkler Jr. moved his family from Atlanta to Miami where he and his wife, Cornelia "Connie" Dinkler, built the posh Palm Bay Club on Biscayne Bay. Just as Dinkler Jr. had been inspired to establish the highly successful restaurant, The Luau (Atlanta's first eatery to offer Polynesian fare), located at 1999 Peachtree Road, the Palm Bay Club was but another well-executed concept stemming from Dinkler's keen business mind. Featuring condominiums and a marina (and later the 27-floor Palm Bay Club Towers), the exclusive development was frequented by many celebrities including Charlton Heston and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

On November 18, 1967, the haven for socialites was even the site of a jewel heist. Two gunmen slipped in, bound and gagged Mr. and Mrs. Dinkler and made off with $350,000 in gems. The Dinklers had just returned to their penthouse from a $1,000-a-plate charity function they had hosted at the Palm Bay Club. One bandit, described as the "polite" one, kissed Mrs. Dinkler on the cheek and whispered, "You can roll over and touch the telephone." As he essentially apologized for robbing the couple, his accomplice, dressed in a tuxedo, said, "That's enough talk, Gary."

In other news, the Palm Bay was a popular stop for a number of prominent politicians who had come to Miami Beach for the 1972 Republican National Convention. CBS journalist Charles Kuralt concluded in a news report, "At Palm Bay Club, there is air of Republican equality---everybody is a millionaire. Mrs. Carling Dinkler's yacht flags spell out 'Nixon Now'."

The Dinkler penthouse was even featured within the pages of the July 8, 1972 issue of Architectural Digest.

In 1982, Mrs. Dinkler died unexpectedly of a heart attack. She was 59. Carling Dinkler Jr. later remarried, leaving behind the 16-acre residential club he and his first wife had founded. At the age of 85, he died in 2005 in his home in Morgantown, West Virginia.

Hotels' Final Fate

With a distinguished list of Dinkler properties scattered across the South, some might wonder what became of the buildings.

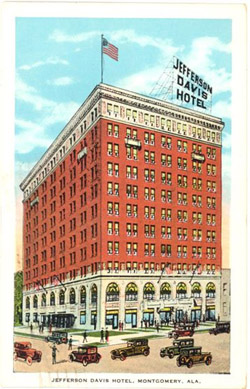

The 11-floor Jefferson Davis Hotel, circa 1929, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, and is now an apartment building. And the Lookout Mountain Hotel is now Covenant College. But other former Dinkler hotels have not been so fortunate.

Atlanta's Dinkler Plaza Hotel was razed in 1972, and the acre of land on which the hotel had been located was sold for a reported $7.7 million in 1988. Beginning in 1967, architect and developer John Portman ushered in a new era, transforming the Atlanta skyline with his awe inspiring Hyatt Regency Hotel (complete with a floor-to-ceiling atrium, glass elevators and its trademark flying saucer-like restaurant). Portman's cylindrical, 73-floor Westin Peachtree Plaza Hotel and the dramatic Marriott Marquis came later, signifying an end to a chapter in Atlanta history in which grand historic hotels (like the Dinkler Plaza/Hotel Ansley, the Piedmont and the Henry Grady) had graced the cityscape with their magnificent architectural presence, exemplifying elegance, tradition and southern hospitality. The age of the sleek, contemporary skyscraper had officially arrived.

However, some 45 years later, Dick Thomas, former Director of Sales for Dinkler Hotels, recounts what he calls "the toughest day I ever had in my life." And his memory of what took place behind closed doors contrasts sharply with the Dinkler Plaza's public assertions. Serving as the Jaycees' national public relations chairman, Thomas recalls the protests and bomb threats that ensued when the news circulated that William D. Johnson "had a suite at the hotel." Even some hotel employees were irate, Thomas says. Shocked that Atlanta, once declared to be the "city too busy to hate," was still experiencing such racial strife in spite of changing views and recent advances, Thomas says the hotel essentially bowed to pressure. To ensure his safety and appease the dissenters, a limousine was summoned, and Johnson (who, as rumored, did have a room at the Dinkler Plaza) was discreetly taken to a black-owned hotel.

Months later, in October 1961, the Dinkler Plaza was the site of a national meeting of Employment Security Program administrators. Citing the hotel's racial policies, 22 states boycotted the event. Marion Williamson, Georgia's Employment Security director, called the racial issue "artificial," but the hotel was once again cast in a negative light, both locally and nationally.

More bad press came in November 1961 when U. S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara traveled to Atlanta to address a segregated audience at the Dinkler Plaza. The New York Times covered McNamara's every move from his arrival at the airport to his cab ride to the hotel. At the last minute, Delta Airlines "diverted the huge Boeing 707 from its designated gate" apparently because of the "presence of Negro demonstrators," the newspaper reported. As McNamara made his way up the concourse, Times reporter Claude Sitton inquired what he thought of the protest, but McNamara denied being aware of the demonstration. Asked to turn his head toward the protesters, McNamara did so and then arrogantly refused to admit he had seen anyone!

A taxi transported McNamara from the airport to a side entrance of the Dinkler Plaza. As he spoke at the dinner honoring U. S. Senator Richard B. Russell and U. S. Representative Carl Vinson, picketers representing the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) protested outside. Holding signs that read "Negroes in the Peace Corps but not the Dinkler" and "Mr. Secretary, you attend this dinner at the expense of human dignity," neither the protesters nor their cause was acknowledged in McNamara's speech. Having attended the event with President John F. Kennedy's apparent blessing, there was much concern within the African American community. After all, blacks had generally supported the Kennedy Administration, but even civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. pondered if Kennedy had "merited the overwhelming support received from Negroes in the last Presidential election."

In March 1962, the NAACP announced plans to hold its annual meeting in Atlanta in July. Expected to draw 1500 to 2000 delegates, the civil rights group vowed to hold the convention regardless of whether Atlanta hotels would accommodate black guests. News of the meeting prompted discussion among members of the Atlanta Hotel Association, and the Dinkler Plaza's own A. J. Crocy (who was also president of the AHA) publicly stated, "Any action taken will come only after long, conscientious deliberations . . . " In the end, the AHA was unrelenting.

"At Your Service"

Like many other southern hoteliers, Dinkler Hotels continued to refuse black guests into the early 1960s, but the company had no qualms about employing African Americans in service positions.

"Maynard Jackson was [once] a waiter at the Dinkler Plaza," Dinkler III recalls, referring to the future Atlanta mayor. In fact, Calvin H. Gibson Sr. (1892-1988), a 60-year employee of Dinkler Hotels and headwaiter for the Dinkler Plaza, hired numerous black college students, including Jackson. "Providing them with jobs that helped pay for their expenses," according to his obituary in the May 19, 1988 Atlanta Constitution, Gibson was noted for his integrity, character and positive effect on young, impressionable students. Crediting Gibson's impact on his life and career, Mayor Jackson said, "He taught me how to wait tables and keep my nose clean, emphasized fine character, clean personal appearance and hard work."

While a student at Clark College, African American Marvin Arrington worked at the Dinkler Plaza under Gibson to earn part of his tuition. An eventual president of the Atlanta City Council, Arrington told the Constitution, "It gave me good work ethics, and he [Gibson] was a part of that growth."

The Turning Point

Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. (1911-2003), a Dinkler family friend, was "credited with leading the city through an era of significant and economic growth" and was "able to broker more peaceful paths to integration," Tammy H. Galloway wrote for the New Georgia Encyclopedia. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution described him as having a "buoyant personality, progressive political style and aristocratic demeanor," and recognized Allen for "bringing major league sports to the South." Undoubtedly, it would take a leader of Allen's stature and charisma to sway hard-line segregationists, and hindsight reveals that his persistence prevailed.

Even though many Atlanta businesses, at Allen's urging, opened their doors to African Americans well before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Dinkler III remembers the adminstration of President Kennedy playing a role in motivating his family to amend its policies regarding the acceptance of black customers.

"Bobby Kennedy called and said, 'Carling, the president would really appreciate it if you would integrate your hotels,' " Dinkler III says. That evening, Dinkler Jr. arrived home from the office and gathered his family together for a meeting. Explaining that the Attorney General had telephoned him about the matter, the family agreed that complying with Kennedy's request would be the right thing to do. "It's gonna cost us money," the elder Dinkler conceded, but Dinkler III says, "We did it anyway."

On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas and, on January 11, 1964, fourteen major Atlanta hotels (including the Dinkler Plaza) announced from Mayor Allen's office their pledge to accept reservations regardless of race (although several had already been quietly accepting black guests).

As Dinkler had predicted, the decision was not without repercussions. Several conventions canceled their reservations, and Dinkler III says a bomb was even placed in the mailbox of the Dinkler family home in Atlanta. Nonetheless, Dinkler Hotels set a positive example, and the family never regretted its decision.

Dinkler Plaza Hotel Site of Historic Banquet

An extraordinary orator and brilliant leader, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. unequivocally impacted the civil rights movement, persevering with organized peaceful protests, in spite of persecutions and numerous setbacks. Violent retaliations against King-led marches attracted attention both nationally and internationally, ultimately drawing sympathy and recruiting allies for the cause. As a result of his tireless labor and advocacy of non-violent demonstration, Dr. King received the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Dr. King, who had been treated like royalty in Oslo upon receiving the Nobel Prize, returned to Atlanta where enthusiasm was lukewarm at best. Initially, ticket sales for a monumental integrated banquet city leaders were holding at the Dinkler Plaza to honor King were fickle, but Coca Cola Company chairman and CEO J. Paul Austin reportedly fostered support and created anticipation for the dinner and, thanks to his bold stand, the banquet tickets were much sought after and sold out quickly.

"More than 1,500 people---the cream of Atlanta's business, civic, political and religious communities---jammed the Dinkler Plaza Hotel downtown for the three-hour affair. Outside, police were on hand to control picketing that never materialized," the Journal-Constitution stated in a 2002 article, reflecting on the January 29, 1964 event.

Reminiscing of the evening, Mayor Ivan Allen Jr., in his book Mayor: Notes on the Sixties (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971.) wrote, "Somebody came up to the Reverend Sam Williams and me and apologized to us that the dinner was going to run about forty-five minutes late because of the unexpectedly large turnout. 'Don't worry about that,' I said. 'My friend Sam Williams has been waiting for a hundred years to get in that ballroom, and forty-five minutes one way or the other isn't going to bother him much.' "

Janice Rothschild Blumberg, widow of Rabbi Jacob Rothschild, described the unforgettable evening in an interview with the Constitution. "At the end, everyone spontaneously joined hands and sang 'We Shall Overcome.' If there were any dry eyes, I didn't see them."

Other Memorable Moments at the Dinkler Plaza

Presidential stays immediately come to mind for Carling Dinkler III when asked which guests he remembers most. According to Dinkler, both Presidents Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson stayed at the Dinkler Plaza. A teenage boy at the time, he especially recalls the occasions because three floors were always rented. For security reasons, the president and his entourage would have one level to themselves, and the immediate floors below and above were off limits to other hotel guests.

James F. "Jimmy" Campbell worked for 35 years as manager of the hotel's bellboy staff. When he died in 2005, at the age of 94, family and friends reminisced of Campbell's days at the Dinkler Plaza. Campbell shook hands with everyone from presidents to celebrities like Bing Crosby. A daughter, Mary Anderson, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, "He met Elvis and got his autograph for me when I was a teenager, and I thought I'd died and gone to heaven." The newspaper reported that Campbell was always eager to share a story about his experiences at the Dinkler Plaza and, from the sound of it, he had quite a few to tell.

The Dinklers Dock in Miami . . . Literally!

Following the sale of the Dinkler hotels and his eventual departure from managing the properties, Carling Dinkler Jr. moved his family from Atlanta to Miami where he and his wife, Cornelia "Connie" Dinkler, built the posh Palm Bay Club on Biscayne Bay. Just as Dinkler Jr. had been inspired to establish the highly successful restaurant, The Luau (Atlanta's first eatery to offer Polynesian fare), located at 1999 Peachtree Road, the Palm Bay Club was but another well-executed concept stemming from Dinkler's keen business mind. Featuring condominiums and a marina (and later the 27-floor Palm Bay Club Towers), the exclusive development was frequented by many celebrities including Charlton Heston and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

On November 18, 1967, the haven for socialites was even the site of a jewel heist. Two gunmen slipped in, bound and gagged Mr. and Mrs. Dinkler and made off with $350,000 in gems. The Dinklers had just returned to their penthouse from a $1,000-a-plate charity function they had hosted at the Palm Bay Club. One bandit, described as the "polite" one, kissed Mrs. Dinkler on the cheek and whispered, "You can roll over and touch the telephone." As he essentially apologized for robbing the couple, his accomplice, dressed in a tuxedo, said, "That's enough talk, Gary."

In other news, the Palm Bay was a popular stop for a number of prominent politicians who had come to Miami Beach for the 1972 Republican National Convention. CBS journalist Charles Kuralt concluded in a news report, "At Palm Bay Club, there is air of Republican equality---everybody is a millionaire. Mrs. Carling Dinkler's yacht flags spell out 'Nixon Now'."

The Dinkler penthouse was even featured within the pages of the July 8, 1972 issue of Architectural Digest.

In 1982, Mrs. Dinkler died unexpectedly of a heart attack. She was 59. Carling Dinkler Jr. later remarried, leaving behind the 16-acre residential club he and his first wife had founded. At the age of 85, he died in 2005 in his home in Morgantown, West Virginia.

Hotels' Final Fate

With a distinguished list of Dinkler properties scattered across the South, some might wonder what became of the buildings.

The 11-floor Jefferson Davis Hotel, circa 1929, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, and is now an apartment building. And the Lookout Mountain Hotel is now Covenant College. But other former Dinkler hotels have not been so fortunate.

Atlanta's Dinkler Plaza Hotel was razed in 1972, and the acre of land on which the hotel had been located was sold for a reported $7.7 million in 1988. Beginning in 1967, architect and developer John Portman ushered in a new era, transforming the Atlanta skyline with his awe inspiring Hyatt Regency Hotel (complete with a floor-to-ceiling atrium, glass elevators and its trademark flying saucer-like restaurant). Portman's cylindrical, 73-floor Westin Peachtree Plaza Hotel and the dramatic Marriott Marquis came later, signifying an end to a chapter in Atlanta history in which grand historic hotels (like the Dinkler Plaza/Hotel Ansley, the Piedmont and the Henry Grady) had graced the cityscape with their magnificent architectural presence, exemplifying elegance, tradition and southern hospitality. The age of the sleek, contemporary skyscraper had officially arrived.

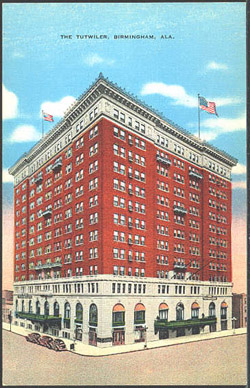

Similarly, the original Tutwiler Hotel in Birmingham was leveled in 1974 to make way for the 17-floor Regions Bank Building. Greensboro's O. Henry Hotel, built in 1919, was replaced by the Bellemeade Street Parking Deck. And the 12-floor Andrew Jackson Hotel, a Nashville fixture dating back to 1925, was demolished, vacating space for the James K. Polk State Office Building.

The Dinkler Legacy

Carling Dinkler III has observed many changes in the hospitality industry and asserts, "When hotels changed from being totally owned by families-be it Hilton or Dinkler-the whole world changed [as far as] how hotels are operated." He adds, "Hotels began losing their innkeeping cache, becoming more of a cash machine, in the 60s."

"You know the more I think about the differences between now and when we were in the business, I cannot help but note that these are really different times with different expectations," Dinkler III reflects. "The world in general is a bit more casual. People wear blue jeans (expensive ones at that), and the coat and tie are going by the wayside. Perhaps we were doing the right thing at the right time. Having said that, I will always believe there is a place for good service and customer care. It just costs a lot of money to provide in these times. I do think the Dinklers were part of the growth of hospitality and, in some ways, its innovation, but we live in times in which ROI (return of investment) and stock value are more important than the proper way to turn down a bed."

Dinkler III does, however, believe the highest levels of quality and service can be expected of certain modern chain hotels, but for a price, as opposed to the days of family-owned hotels like the Dinkler properties where "it was a given."

Noting the evolving hospitality industry and a desire to pursue a career path of his own, Carling Dinkler III opted not to become a hotelier. He moved from Atlanta to New Orleans where he operated an airport shuttle service and later owned the New Orleans Gray Line sightseeing tour franchise. A founder of the New Orleans Convention and Visitors Bureau, Dinkler III eventually carved out a successful niche in the convention business with his lucrative destination management venture, Custom Conventions. Operating in the "Crescent City" and Las Vegas, the company can coordinate and facilitate virtually every aspect of a client's meeting or conference.

Carling Dinkler IV (b. 1979) also has taken a divergent path, working on Capitol Hill in Washington from 2003 to 2010 as a legislative assistant before returning to New Orleans to become an account manager for Laitrum Machinery. In addition to his work with U. S. Representatives Chris John and John Tanner, Dinkler IV campaigned vigorously for Louisiana Lieutenant Governer Mitch Landrieu in his challenge against incumbent Ray Nagin in the 2006 New Orleans mayoral race.

Though their hotels have faded into memory, the story of the Dinklers is the American experience epitomized. An immigrant makes a life for himself, and successive generations inherit his work ethic and tenacity, ultimately shaping Atlanta and an entire industry because of their diligence and influence.

The Dinkler Legacy

Carling Dinkler III has observed many changes in the hospitality industry and asserts, "When hotels changed from being totally owned by families-be it Hilton or Dinkler-the whole world changed [as far as] how hotels are operated." He adds, "Hotels began losing their innkeeping cache, becoming more of a cash machine, in the 60s."

"You know the more I think about the differences between now and when we were in the business, I cannot help but note that these are really different times with different expectations," Dinkler III reflects. "The world in general is a bit more casual. People wear blue jeans (expensive ones at that), and the coat and tie are going by the wayside. Perhaps we were doing the right thing at the right time. Having said that, I will always believe there is a place for good service and customer care. It just costs a lot of money to provide in these times. I do think the Dinklers were part of the growth of hospitality and, in some ways, its innovation, but we live in times in which ROI (return of investment) and stock value are more important than the proper way to turn down a bed."

Dinkler III does, however, believe the highest levels of quality and service can be expected of certain modern chain hotels, but for a price, as opposed to the days of family-owned hotels like the Dinkler properties where "it was a given."

Noting the evolving hospitality industry and a desire to pursue a career path of his own, Carling Dinkler III opted not to become a hotelier. He moved from Atlanta to New Orleans where he operated an airport shuttle service and later owned the New Orleans Gray Line sightseeing tour franchise. A founder of the New Orleans Convention and Visitors Bureau, Dinkler III eventually carved out a successful niche in the convention business with his lucrative destination management venture, Custom Conventions. Operating in the "Crescent City" and Las Vegas, the company can coordinate and facilitate virtually every aspect of a client's meeting or conference.

Carling Dinkler IV (b. 1979) also has taken a divergent path, working on Capitol Hill in Washington from 2003 to 2010 as a legislative assistant before returning to New Orleans to become an account manager for Laitrum Machinery. In addition to his work with U. S. Representatives Chris John and John Tanner, Dinkler IV campaigned vigorously for Louisiana Lieutenant Governer Mitch Landrieu in his challenge against incumbent Ray Nagin in the 2006 New Orleans mayoral race.

Though their hotels have faded into memory, the story of the Dinklers is the American experience epitomized. An immigrant makes a life for himself, and successive generations inherit his work ethic and tenacity, ultimately shaping Atlanta and an entire industry because of their diligence and influence.

No longer a Birmingham landmark, courtesy of "progress" and the wrecking ball, the original Tutwiler Hotel (built in 1914 at 20th Street and 5th Avenue North), pictured above, is not to be confused with Birmingham's current Tutwiler Hotel (formerly the Ridgeley Apartments, built one year earlier and located at 2021 Park Place North).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frederick Allen, Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City 1946-1996 (Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1996).

Ivan Allen Jr., Mayor: Notes on the Sixties (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971).

Holly Crenshaw, "Obituaries: ATLANTA, J. F. Campbell, 94, met city's famous writers," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 5, 2005.

Mae Gentry, "NOBEL PEACE PRIZE: In 1964, award to King stirred a storm," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 10, 2002.

Paul Jones, "Dinklers Lease Piedmont Hotel: Big Sum Involved," Atlanta Constitution, December 2, 1923.

Monique Logan, "Calvin Gibson Sr., was headwaiter who gave black students hotel jobs," Atlanta Journal, May 19, 1988.

Alan Patureau, "Grand reminders of Atlanta's past are getting five-star treatment," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 2, 1991.

Sallye Salter, "Equitable, Japanese Partner to Pay $7.7 Million for One Acre Downtown," Atlanta Journal, August 16, 1988.

Claude Sitton, "22 States Shun Job Conference," The New York Times, October 3, 1961.

Claude Sitton, "McNamara Talks Despite Protest," The New York Times, November 12, 1961.

Ernie Suggs, "Portrait of Dignity: Coretta Scott King/1927-2006: 'She's at peace now'," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 1, 2006.

Ernie Suggs and Tom Bennett, "Shaper of Modern Atlanta: Ivan Allen Jr.: 1911-2003: Foundation building the new Atlanta," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 3, 2003.

Alfred Wright, "Connie's Club for Homeless Glitterbugs," Sports Illustrated, December 13, 1965.

"Andrew Jackson Hotel," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

"Atlanta Hotels Drop Color Line," The New York Times, January 12, 1964.

"Carling Hotel," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

"Dinkler Sells Hotels," The New York Times, February 25, 1961.

"Final Rites Today For Louis Dinkler," Atlanta Constitution, December 2, 1928.

"Hotel Ansley," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

"Hotel Head Dies in 12-story Fall," The New York Times, January 31, 1961.

"Ivan Allen Jr. (1911-2003)," New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.newgeorgiaencyclopedia.org.

"Jefferson Davis Hotel," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

"L. J. Dinkler Ends Life with Bullet," Atlanta Constitution, December 1, 1928.

"Louis Dinkler Invites Public To See Hotel," Macon Weekly Telegraph, July 9, 1911.

"NAACP Creates Atlanta Problem," The New York Times, March 11, 1962.

"Negro Jaycees Not Registered, Hotel Asserts," Atlanta Constitution, January 20, 1961.

"New Orleans Hotel Sold," The New York Times, August 3, 1959.

"Two Bandits in Miami Get $350,000 Gems," The New York Times, November 18, 1967.

"Tutwiler Hotel," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

OTHER SOURCES

Telephone conversations and electronic communications with Carling Dinkler III, New Orleans/Las Vegas, May and June 2006.

Telephone conversation with Inman Allen, Atlanta, May 2006.

Telephone conversation with Dick Thomas, Las Vegas, May 2006.

Author: Greg Freeman. Published June 17, 2006. Revised August 15, 2008 and August 25, 2009. Revised June 9, 2012.

Frederick Allen, Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City 1946-1996 (Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1996).

Ivan Allen Jr., Mayor: Notes on the Sixties (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971).

Holly Crenshaw, "Obituaries: ATLANTA, J. F. Campbell, 94, met city's famous writers," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 5, 2005.

Mae Gentry, "NOBEL PEACE PRIZE: In 1964, award to King stirred a storm," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 10, 2002.

Paul Jones, "Dinklers Lease Piedmont Hotel: Big Sum Involved," Atlanta Constitution, December 2, 1923.

Monique Logan, "Calvin Gibson Sr., was headwaiter who gave black students hotel jobs," Atlanta Journal, May 19, 1988.

Alan Patureau, "Grand reminders of Atlanta's past are getting five-star treatment," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 2, 1991.

Sallye Salter, "Equitable, Japanese Partner to Pay $7.7 Million for One Acre Downtown," Atlanta Journal, August 16, 1988.

Claude Sitton, "22 States Shun Job Conference," The New York Times, October 3, 1961.

Claude Sitton, "McNamara Talks Despite Protest," The New York Times, November 12, 1961.

Ernie Suggs, "Portrait of Dignity: Coretta Scott King/1927-2006: 'She's at peace now'," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 1, 2006.

Ernie Suggs and Tom Bennett, "Shaper of Modern Atlanta: Ivan Allen Jr.: 1911-2003: Foundation building the new Atlanta," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 3, 2003.

Alfred Wright, "Connie's Club for Homeless Glitterbugs," Sports Illustrated, December 13, 1965.

"Andrew Jackson Hotel," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

"Atlanta Hotels Drop Color Line," The New York Times, January 12, 1964.

"Carling Hotel," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

"Dinkler Sells Hotels," The New York Times, February 25, 1961.

"Final Rites Today For Louis Dinkler," Atlanta Constitution, December 2, 1928.

"Hotel Ansley," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

"Hotel Head Dies in 12-story Fall," The New York Times, January 31, 1961.

"Ivan Allen Jr. (1911-2003)," New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.newgeorgiaencyclopedia.org.

"Jefferson Davis Hotel," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

"L. J. Dinkler Ends Life with Bullet," Atlanta Constitution, December 1, 1928.

"Louis Dinkler Invites Public To See Hotel," Macon Weekly Telegraph, July 9, 1911.

"NAACP Creates Atlanta Problem," The New York Times, March 11, 1962.

"Negro Jaycees Not Registered, Hotel Asserts," Atlanta Constitution, January 20, 1961.

"New Orleans Hotel Sold," The New York Times, August 3, 1959.

"Two Bandits in Miami Get $350,000 Gems," The New York Times, November 18, 1967.

"Tutwiler Hotel," Emporis. Retrieved May 2006: http://www.emporis.com.

OTHER SOURCES

Telephone conversations and electronic communications with Carling Dinkler III, New Orleans/Las Vegas, May and June 2006.

Telephone conversation with Inman Allen, Atlanta, May 2006.

Telephone conversation with Dick Thomas, Las Vegas, May 2006.

Author: Greg Freeman. Published June 17, 2006. Revised August 15, 2008 and August 25, 2009. Revised June 9, 2012.

Copyright

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

All materials contained on this site, including text and images, are protected by copyright laws and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. Where applicable, use of some items contained on this site may require permission from other copyright owners.

Fair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.

Contact Greg Freeman or SouthernEdition.comFair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.