Southern Exposure

Still The Uncrowned Queen?

A Retrospect of North Georgia's Own Ida Cox

A Retrospect of North Georgia's Own Ida Cox

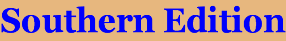

Born Ida Prather on February 25, 1896 in Toccoa, Georgia, the future blues legend and her family left what is now Stephens County when she was quite young, moving to Lawrenceville before finally settling in Cedartown. As a teenager, she ran away from home to travel the South with a minstrel revue, performing in vaudeville houses and tent shows.

Ida Cox descended from slaves owned by a very prominent family in the Toccoa area, hence her maiden name. The Prathers possessed vast amounts of real estate, operated cotton gins and, among other enterprises, farmed the bottoms along the Tugaloo River (a Savannah River tributary now part of Hartwell Reservoir).

Mrs. Edna Prather, wife of the late Joseph T. Prather (son of Senator James Devereaux Prather), indicates the family had "owned over a thousand acres along the Tugaloo" on which they grew corn and cotton. She recounts that it was her husband's grandfather, Joseph Jeremiah Prather, who utilized slave labour. Today, Mrs. Prather resides at Riverside, the Greek Revival house originally built by Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Jeremiah Prather around 1854.

With a humble beginning, reportedly along Toccoa's Prather Bridge Road, Ida Cox would eventually perform in metropolises such as Chicago and New York.

Could the little black girl, with Georgia red clay between her toes, have envisioned the glamorous career that awaited? Whether or not she dreamed of "making it," history reveals her unique style and charisma propelled her to a degree of success equaled or exceeded by only a few and envied by countless others at that time.

The Birth of Blues

In the early 1900s, vaudeville was a popular entertainment form, uniquely highlighting music, dance, comedy and other performances in separate, independent acts. It would later decline with the introduction of sound motion pictures, but several vaudeville singers would somewhat reinvent themselves and subsequently become the founders of the blues genre as we know it. One of those founders was Ida Cox.

While recording technology at that time was quite primitive compared to today's premier studios in New York, London, Los Angeles and Nashville, the early blues recordings, distributed by "race" labels, were well received, stimulating commercial success and even some critical acclaim.

However, it was certainly a different era, and any fame or fortune garnered at that time would hardly rival the attention lavished upon our current black female music stars such as singer-actress Whitney Houston, pop/jazz sensation Natalie Cole or urban/R&B prodigy Alicia Keyes.

Before blues was guitar driven and male dominated (à la John Lee Hooker and B. B. King), the field was firmly established by a handful of black women accompanied by pianists.

Among these were the flamboyant , dangerous-living "Empress of the Blues," Bessie Smith, and the incomparable Ma Rainey who interestingly toured briefly with Georgia Tom backing her on the piano. (Thomas A. Dorsey, aka Georgia Tom, would later experience a religious conversion, pen such gospel classics as "Peace in the Valley" and "Precious Lord, Take My Hand" and be hailed as the "Father of Gospel Music.")

As for Ida Cox, she, too, worked the circuit with pianists like Jelly Roll Morton, performing at the 81 Theater in Atlanta and Tom Anderson's Cafe in New Orleans as well as appearing on Memphis' WMC Radio.

Having divorced her first husband, Adler Cox (of the Florida Blossom Minstrel Show), she later married Texas piano man Jesse "Tiny" Crump. It was during this time that she was discovered and signed to a recording contract by Paramount Records' talent scout, Mayo Williams. This college-educated black man was instrumental in launching the careers of several blues artists including the aforementioned Ma Rainey.

Ida Cox descended from slaves owned by a very prominent family in the Toccoa area, hence her maiden name. The Prathers possessed vast amounts of real estate, operated cotton gins and, among other enterprises, farmed the bottoms along the Tugaloo River (a Savannah River tributary now part of Hartwell Reservoir).

Mrs. Edna Prather, wife of the late Joseph T. Prather (son of Senator James Devereaux Prather), indicates the family had "owned over a thousand acres along the Tugaloo" on which they grew corn and cotton. She recounts that it was her husband's grandfather, Joseph Jeremiah Prather, who utilized slave labour. Today, Mrs. Prather resides at Riverside, the Greek Revival house originally built by Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Jeremiah Prather around 1854.

With a humble beginning, reportedly along Toccoa's Prather Bridge Road, Ida Cox would eventually perform in metropolises such as Chicago and New York.

Could the little black girl, with Georgia red clay between her toes, have envisioned the glamorous career that awaited? Whether or not she dreamed of "making it," history reveals her unique style and charisma propelled her to a degree of success equaled or exceeded by only a few and envied by countless others at that time.

The Birth of Blues

In the early 1900s, vaudeville was a popular entertainment form, uniquely highlighting music, dance, comedy and other performances in separate, independent acts. It would later decline with the introduction of sound motion pictures, but several vaudeville singers would somewhat reinvent themselves and subsequently become the founders of the blues genre as we know it. One of those founders was Ida Cox.

While recording technology at that time was quite primitive compared to today's premier studios in New York, London, Los Angeles and Nashville, the early blues recordings, distributed by "race" labels, were well received, stimulating commercial success and even some critical acclaim.

However, it was certainly a different era, and any fame or fortune garnered at that time would hardly rival the attention lavished upon our current black female music stars such as singer-actress Whitney Houston, pop/jazz sensation Natalie Cole or urban/R&B prodigy Alicia Keyes.

Before blues was guitar driven and male dominated (à la John Lee Hooker and B. B. King), the field was firmly established by a handful of black women accompanied by pianists.

Among these were the flamboyant , dangerous-living "Empress of the Blues," Bessie Smith, and the incomparable Ma Rainey who interestingly toured briefly with Georgia Tom backing her on the piano. (Thomas A. Dorsey, aka Georgia Tom, would later experience a religious conversion, pen such gospel classics as "Peace in the Valley" and "Precious Lord, Take My Hand" and be hailed as the "Father of Gospel Music.")

As for Ida Cox, she, too, worked the circuit with pianists like Jelly Roll Morton, performing at the 81 Theater in Atlanta and Tom Anderson's Cafe in New Orleans as well as appearing on Memphis' WMC Radio.

Having divorced her first husband, Adler Cox (of the Florida Blossom Minstrel Show), she later married Texas piano man Jesse "Tiny" Crump. It was during this time that she was discovered and signed to a recording contract by Paramount Records' talent scout, Mayo Williams. This college-educated black man was instrumental in launching the careers of several blues artists including the aforementioned Ma Rainey.

Cox's Career Gets Underway

Ida Cox's first records for Paramount, "Graveyard Dream Blues" and "Weary Way Blues," were recorded in the summer of 1923. In seven years, she recorded 78 songs. Bearing in mind that Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey were highly in vogue, Paramount promoted Cox as the "Uncrowned Queen of the Blues."

An astute businesswoman, Cox served as her own manager and producer, and was a prolific songwriter. She addressed many of the relevant issues affecting her core audience, the impoverished, oppressed black women who felt restrained by the yoke of inequality, damned by racial injustices and hopelessly trapped with little with which to aspire.

Of course, no one ever said the blues are pretty! Many of her songs contained death themes, including "Black Crepe Blues," "Bone Orchard Blues," "Cemetery Blues," "Coffin Blues," "Cold Black Ground Blues," "Death Letter Blues," "Graveyard Bound Blues" and "Marble Stone Blues."

Ida Cox's first records for Paramount, "Graveyard Dream Blues" and "Weary Way Blues," were recorded in the summer of 1923. In seven years, she recorded 78 songs. Bearing in mind that Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey were highly in vogue, Paramount promoted Cox as the "Uncrowned Queen of the Blues."

An astute businesswoman, Cox served as her own manager and producer, and was a prolific songwriter. She addressed many of the relevant issues affecting her core audience, the impoverished, oppressed black women who felt restrained by the yoke of inequality, damned by racial injustices and hopelessly trapped with little with which to aspire.

Of course, no one ever said the blues are pretty! Many of her songs contained death themes, including "Black Crepe Blues," "Bone Orchard Blues," "Cemetery Blues," "Coffin Blues," "Cold Black Ground Blues," "Death Letter Blues," "Graveyard Bound Blues" and "Marble Stone Blues."

Typical of that era, several Cox songs were blatantly risque ("Handy Man" and "One Hour Mama") while others were related to geographical locations including "Memphis Tennessee," "The West Texas Blues," "Birmingham Blues," "Pensacola Blues" and "Muscle Shoals Blues."

As with today's ever-changing music trends and short-lived careers, the popularity of blues waned with the beginning of the 'Big Band' craze, and Cox's heyday was apparently over following the Depression years. Or was it?

From Toccoa to Carnegie Hall

On December 23, 1938, John Hammond, a white record producer, indelibly made music history with his presentation of From Spirituals to Swing---an unprecedented event which featured a remarkably diverse set (blues, jazz, gospel, etc.) performed by some of the most gifted black artists of the times before an enthusiastic, integrated audience. The sold-out concert was held at a prestigious venue (you might have heard of it!) located on New York's Seventh Avenue and 57th Street.

Again, in 1939, the second and final From Spirituals to Swing concert familiarized its attendees with some future legends in the making. Many of the fans were perhaps only beginning to understand and appreciate black music as an art form, and the reintroduction of an original, female blues star of the 1920s must have surely been an evening highlight as she sang "Lowdown Dirty Shame" and " 'Fore Day Creep" with fervor, resonance and the authenticity of a diva. Ida Cox had made it all the way to Carnegie Hall!

As with today's ever-changing music trends and short-lived careers, the popularity of blues waned with the beginning of the 'Big Band' craze, and Cox's heyday was apparently over following the Depression years. Or was it?

From Toccoa to Carnegie Hall

On December 23, 1938, John Hammond, a white record producer, indelibly made music history with his presentation of From Spirituals to Swing---an unprecedented event which featured a remarkably diverse set (blues, jazz, gospel, etc.) performed by some of the most gifted black artists of the times before an enthusiastic, integrated audience. The sold-out concert was held at a prestigious venue (you might have heard of it!) located on New York's Seventh Avenue and 57th Street.

Again, in 1939, the second and final From Spirituals to Swing concert familiarized its attendees with some future legends in the making. Many of the fans were perhaps only beginning to understand and appreciate black music as an art form, and the reintroduction of an original, female blues star of the 1920s must have surely been an evening highlight as she sang "Lowdown Dirty Shame" and " 'Fore Day Creep" with fervor, resonance and the authenticity of a diva. Ida Cox had made it all the way to Carnegie Hall!

The End of the Beginning

With the emergence of more contemporary, fancy-picking, blues guitarists, a diminished interest in '20s style music and her suffering of a stroke, Cox opted to forsake the blues altogether. She eventually moved to Knoxville in 1949 where she assumed a low profile and lived out the last years of her life with her daughter, Helen Goode, in a modest residence on Louise Avenue.

Having renewed her faith in God, Cox's performances were strictly limited to singing in the Patton Street Church of God choir. Her fellow choir members were probably unaware of who she truly was!

While Ida Cox was living contently without fanfare, Chris Albertson at Riverside Records (label home of Cannonball Adderley and Thelonious Monk) in New York persuaded company owners Bill Grauer and Orrin Keepnews to permit him to track down Cox in an attempt to convince her to record an album. At the airport prior to his flight's departure, Albertson telephoned the retired blues singer's old friend, John Hammond, an executive at Columbia Records. Hammond provided Albertson with Cox's contact information, and the trip to Knoxville proved worthwhile, to say the least.

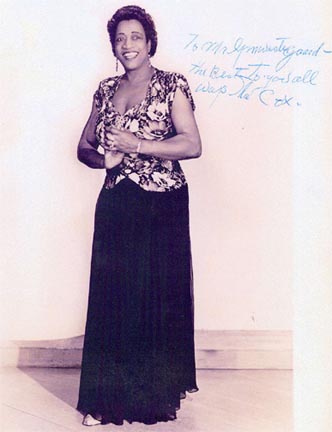

Ida Cox was eventually swayed to come to New York to record what would be her final project. Blues for Rampart Street, produced by Albertson and recorded in April 1961 at Plaza Sound Studios atop New York's famed Radio City Music Hall, included an all-star band featuring saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and trumpeteer Roy Eldridge.

Along about the same time arrangements were being made for Cox to record in New York, Knoxville television and radio announcer Lynn Westergaard (son of radio personality R. B. "Dick" Westergaard) learned from his friend, musician Harry Nides, that Ida Cox was living just minutes away in East Knoxville. Westergaard, 24, met Cox, recorded an interview with her and became quite the devotee. He traveled to New York, and was allowed to be present during the recording sessions. "She did several of the selections on the first take," Westergaard recalls.

While in New York, Ida Cox was a main attraction, even appearing on Merv Griffin's NBC quiz show, Play Your Hunch. The blindfolded contestants were unsuccessful in guessing who was belting out "Put Your Arms Around Me, Honey, Hold Me Tight."

Indeed, a star had come to town and anything less than celebrity treatment would have been insulting.

Whitney Balliett, a reporter for The New Yorker, wrote, "Guess who was in and out of town last week, and after a 20-year absence, at that!" During Balliet's interview with the singer in her room at the Paramount Hotel, Cox doused the flames of speculation that her recording career might rebound by clearly stating, "I mean to do the best that I can. But then I'm going back home---whoom, like that."

In other interviews, Cox would later express some concerns over her last recording, even indicating she prayed for God's forgiveness if her momentary return to blues was a sin.

Ida Cox Dies at 71

Succumbing to cancer, her life came to an end on Friday, November 10, 1967 at 11:47 p.m. at Knoxville's Baptist Hospital. "I was with Ida just a couple of days before she died," says Westergaard (now a resident of Atlanta) who, four decades later, fondly reminisces about the friendship he was privliged to share with the blues legend.

Her Music Lives On

Certainly some of the sides Ida Cox recorded are vibrant in the contemporary music scene including her most famous composition, "Wild Women Don't Have the Blues," which has become the signature song for Atlanta R&B singer, Francine Reed.

Known for her distinctive, gritty, soulful delivery, Reed could have given those early barrel-house mamas a run for their money! Needless to say, she excels in acquainting audiences with the blues of yesterday through her own interpretations, regularly touring with Curb/Lost Highway recording artist, Lyle Lovett & His Large Band, as well as performing at various Atlanta clubs.

With the emergence of more contemporary, fancy-picking, blues guitarists, a diminished interest in '20s style music and her suffering of a stroke, Cox opted to forsake the blues altogether. She eventually moved to Knoxville in 1949 where she assumed a low profile and lived out the last years of her life with her daughter, Helen Goode, in a modest residence on Louise Avenue.

Having renewed her faith in God, Cox's performances were strictly limited to singing in the Patton Street Church of God choir. Her fellow choir members were probably unaware of who she truly was!

While Ida Cox was living contently without fanfare, Chris Albertson at Riverside Records (label home of Cannonball Adderley and Thelonious Monk) in New York persuaded company owners Bill Grauer and Orrin Keepnews to permit him to track down Cox in an attempt to convince her to record an album. At the airport prior to his flight's departure, Albertson telephoned the retired blues singer's old friend, John Hammond, an executive at Columbia Records. Hammond provided Albertson with Cox's contact information, and the trip to Knoxville proved worthwhile, to say the least.

Ida Cox was eventually swayed to come to New York to record what would be her final project. Blues for Rampart Street, produced by Albertson and recorded in April 1961 at Plaza Sound Studios atop New York's famed Radio City Music Hall, included an all-star band featuring saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and trumpeteer Roy Eldridge.

Along about the same time arrangements were being made for Cox to record in New York, Knoxville television and radio announcer Lynn Westergaard (son of radio personality R. B. "Dick" Westergaard) learned from his friend, musician Harry Nides, that Ida Cox was living just minutes away in East Knoxville. Westergaard, 24, met Cox, recorded an interview with her and became quite the devotee. He traveled to New York, and was allowed to be present during the recording sessions. "She did several of the selections on the first take," Westergaard recalls.

While in New York, Ida Cox was a main attraction, even appearing on Merv Griffin's NBC quiz show, Play Your Hunch. The blindfolded contestants were unsuccessful in guessing who was belting out "Put Your Arms Around Me, Honey, Hold Me Tight."

Indeed, a star had come to town and anything less than celebrity treatment would have been insulting.

Whitney Balliett, a reporter for The New Yorker, wrote, "Guess who was in and out of town last week, and after a 20-year absence, at that!" During Balliet's interview with the singer in her room at the Paramount Hotel, Cox doused the flames of speculation that her recording career might rebound by clearly stating, "I mean to do the best that I can. But then I'm going back home---whoom, like that."

In other interviews, Cox would later express some concerns over her last recording, even indicating she prayed for God's forgiveness if her momentary return to blues was a sin.

Ida Cox Dies at 71

Succumbing to cancer, her life came to an end on Friday, November 10, 1967 at 11:47 p.m. at Knoxville's Baptist Hospital. "I was with Ida just a couple of days before she died," says Westergaard (now a resident of Atlanta) who, four decades later, fondly reminisces about the friendship he was privliged to share with the blues legend.

Her Music Lives On

Certainly some of the sides Ida Cox recorded are vibrant in the contemporary music scene including her most famous composition, "Wild Women Don't Have the Blues," which has become the signature song for Atlanta R&B singer, Francine Reed.

Known for her distinctive, gritty, soulful delivery, Reed could have given those early barrel-house mamas a run for their money! Needless to say, she excels in acquainting audiences with the blues of yesterday through her own interpretations, regularly touring with Curb/Lost Highway recording artist, Lyle Lovett & His Large Band, as well as performing at various Atlanta clubs.

Chris Albertson Recalls Ida Cox and Her Final Recording Sessions

Born in Iceland in 1931, Chris Albertson studied art in Copenhagen before making his way to the United States in the 1950s. He initially worked as a disc jockey in Philadelphia and then relocated to New York to eventually become a noted record producer, author, jazz journalist and two-time Grammy winner. Critically acclaimed Bessie (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2003 rev. ed.) is his authoritative biography of blues legend Bessie Smith. Albertson was the producer of Ida Cox's final recording project, Blues for Rampart Street, an album he persuaded her to record for New York-based Riverside Records in 1961 . Shedding light on his visit with Ida Cox in Knoxville and her final recording sessions in New York, Chris Albertson recounts his time with the blues singer as follows:

Chris Albertson: I went down there, and I called her from my hotel. She said, "I don't sing anymore except in church." She was very nice, and she said, "Why don't you come by?" She was living with her daughter in a very nice section of Knoxville, and I went up there and we got along very well. She said she wasn't going to sing. She was finished with that part of her life. Then I brought up all these people she had worked with and all her old recordings, and got her on course for a nostalgia trip, I guess. (Laughing) She finally said, "Well, you know? Maybe just one." I didn't know it then, but she thought we were still doing 78s. (Laughing)

Greg Freeman: Oh! She didn't know she was going to do an entire album. (Laughing)

C. A.: Right.

G. F.: (Laughing)

C. A.: She thought [it would be] two- or three-minute sides like they did in the old days. I didn't realize that until she got to New York. But, anyway, her health was not the best. And she had a doctor she was seeing regularly, and she put me in touch with the doctor.

Oh, and she had a neighbor who played piano, and I knew she could still sing 'cause she did do that. Her daughter sent me a tape of her singing with the neighbor accompanying her, and I think it had been done fairly recently, but it might not have been. Anyway, I wouldn't worry about that. But when I got to New York, I was in regular contact with her doctor, and I think it was maybe a couple of months before he finally said, "She's okay. She can go now." And, of course, she didn't know who I was, and she was leery of all that . . . this stranger from New York.

G. F.: Oh, sure.

C. A.: I talked to Grauer and said, "Can we send her a check in advance? So, of course, we sent her a ticket and all that, but we also sent her a check. I think it was $750. I may be wrong. But, anyway, she came.

Our offices were in the Paramount Hotel, which is right in the theatre district. And so we got her a room there, and I pretty much stayed with her most all of the time except when she was sleeping. I would sit in her room and watch television with her.

And then she wanted to buy a dress for her daughter. So, we had a young lady, then a composer, who [eventually] committed suicide, a real nice lady . . . Sarah Cassey. And Sarah said, "Let me take her out." And Sarah knew where to go, you know. And that was one of the few times when I wasn't with her.

G. F.: Sure.

C. A.: But I was supposed to meet them at one point at the Metropole Cafe after they went out shopping. And I remember going into the Metropole Cafe, and Henry "Red" Allen was there. And I said, "Have you seen Ida Cox?" And he said, "Where are you coming from, man? She's been dead for years!" He thought she was dead. (Laughing)

The funniest thing happened when . . .

One of the last live performances she'd given was with Count Basie's band in the '40s. And Basie was at the Apollo. So, I asked if she wanted to go there. And, of course, she had appeared at the Apollo and wanted to go there.

So, we went there and went backstage, and Basie was in the dressing room. The dressing rooms there aren't anything to write home about, but the star dressing room was bigger than the others. So, he's facing the wall, facing a mirror, and the door is behind him. He could see who was coming in by looking at the mirror. And we came in. He looked, and he looked, and turned around. "Ida?" "Yes, honey." He [then] said, "Didn't you die?"

G. F.: (Laughing)

C. A.: She said, "Honey, I came back."

G. F.: (Laughing) That's great.

C. A.: "Didn't you die" is my favorite line.

Anyway, when we got into the studio, we did two sessions. Two days in a row and, of course, had an all-star band.

I spent a lot of time in the session transcribing from the old Paramount records because she couldn't remember the lyrics. Some of those records were very old and difficult to understand the lyrics, but I did that, at any rate . . . typed out for her. We got into the studio, and I would hand her the sheet with the lyrics, and she would read maybe the first line or two, and then her hand dropped as it all came back to her.

G. F.: Wow! And this was recorded at Radio City Music Hall, correct?

C. A.: Well, no, it was at the Plaza Sound Studios, which were atop Radio City Music Hall. You went through a side entrance.

G. F.: Okay.

C. A.: I took her into the control room, and she saw the row of Ampex tape recorders and said, "Are we gonna record both sides today?" So, I told her, "We don't just record two sides." I explained to her what an LP was, and she just went, "Mmm. Mmm. Mmm. Isn't that marvelous?" (Laughing)

And, so she was very impressed with the orchestra. Of course, these were not young guys. Coleman Hawkins had been a member of Ma Rainey's band when he was young. But she said, "Those kids are good."

G. F.: Those kids! (Laughing)

C. A.: And the place was packed. Balliett. Nat Hentoff. Martin Williams. John S. Wilson of The New York Times. Every major critic in town called and wanted to come there.

It was an event.

In fact, Lovett's 1999 CD, Live in Texas, features Francine Reed in a roof-raising rendition of Cox's "Wild Women." The boisterous cheers in the crowd are likely coming from Reed's female fans reveling at the notion of living loose and easy, essentially trampling over any socially ingrained inhibitions. One has to wonder how Ida Cox fans reacted to this song seven decades ago!

With All Due Respect . . .

It is doubtful that most Toccoans were aware of Ida Cox's appearance at Carnegie Hall in 1939. Considering the attitudes of the day, most probably wouldn't have cared!

Yet, in the middle of it all, a talented, ambitious "colored" girl from a small North Georgia town set out to pursue a better life despite the limitations and hardships she would inevitably face.

Rising to national prominence in her field, Ida Cox was both a pioneer and icon, by all accounts, securing a significant place in America's rich and illustrious musical past.

However, some students of roots music contend that artists such as Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey and Ida Cox have been slighted in recent blues documentaries, including Martin Scorsese Presents The Blues---A Musical Journey on PBS, in which a great deal of emphasis was placed on the male guitarists from the Mississippi Delta.

Joseph Johnson, Curator of Music & Popular Culture at the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in Macon, concurs. "These female preachers of the blues have not received the credit and attention they deserve for putting blues on record," he says, adding their careers "were concurrent with all those Delta guys."

A Lesson Worth Learning

Most Georgians today have probably not even heard of Ida Cox---even older members of the African American community. In stark contrast, she is revered by musicologists.

The U. S. Congress had declared 2003 the "Year of the Blues," but little homage was paid to this important blues figure. Perhaps now is a fitting time to re-explore Cox's musical path and discover what makes her story worth remembering.

She triumphed despite social hurdles, racial barriers and the Great Depression.

Somewhere amid the Ida Cox journey echoes a sublime, inspiring theme, pulsating to the infectious groove of a ragtime melody, reassuring a new generation that life can surely be pursued to the fullest extent given the opportunities accessible today.

MUSIC SOURCES

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, 1923, Volume 1, DOCD-5322, Document Records.

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works 1924-1925 in Chronological Order, Volume 2, DOCD-5323, Document Records.

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works 1925-1927 in Chronological Order, Volume 3, DOCD-5324, Document Records.

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works 1927-1938 in Chronological Order, Volume 4, DOCD-5325, Document Records.

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works 1939-1940 in Chronological Order,

Volume 5, DOCD-5651, Document Records.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Whitney Balliett, "Talk of the Town: 'Yes Yes Yes Yes'," The New Yorker, April 29, 1961.

Robert Booker, "Ida Cox: star blues singer before retiring here," Knoxville Journal, April 13, 1989.

Jack Neely, "Whoom, Like That," Metropulse, February 1-8, 1996.

Jack Neely, "The Secret Diva of Louise Avenue," Metropulse, February 24, 2000.

Robert Santelli, The Big Book of Blues: A Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Penguin Group, 2001).

Robert Santelli, Holly George-Warren and Jim Brown, eds., American Roots Music (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001).

Bill Wyman, Bill Wyman's Blues Odyssey: A Journey to Music's Heart & Soul (New York: Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc., 2001).

"Obituary: COX, Mrs. Ida," Knoxville News-Sentinel, November 12, 1967.

OTHER SOURCES

Telephone conversation with Mrs. Edna Prather, Toccoa, Georgia, on May 23, 2003

Telephone conversation with Joseph Johnson, Georgia Music Hall of Fame, Macon, Georgia, Summer 2003

Telephone conversation with Lynn Westergaard, Atlanta, on November 9, 2003

Telephone conversation with Chris Albertson, New York, on August 8, 2008

*Special thanks to Jamie Osborn, Reference Assistant, McClung Historical Collection, Knox County Public Library System, Knoxville, for his assistance, October 2003

Author: Greg Freeman. Published May 7, 2006. Revised August 9, 2008.

With All Due Respect . . .

It is doubtful that most Toccoans were aware of Ida Cox's appearance at Carnegie Hall in 1939. Considering the attitudes of the day, most probably wouldn't have cared!

Yet, in the middle of it all, a talented, ambitious "colored" girl from a small North Georgia town set out to pursue a better life despite the limitations and hardships she would inevitably face.

Rising to national prominence in her field, Ida Cox was both a pioneer and icon, by all accounts, securing a significant place in America's rich and illustrious musical past.

However, some students of roots music contend that artists such as Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey and Ida Cox have been slighted in recent blues documentaries, including Martin Scorsese Presents The Blues---A Musical Journey on PBS, in which a great deal of emphasis was placed on the male guitarists from the Mississippi Delta.

Joseph Johnson, Curator of Music & Popular Culture at the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in Macon, concurs. "These female preachers of the blues have not received the credit and attention they deserve for putting blues on record," he says, adding their careers "were concurrent with all those Delta guys."

A Lesson Worth Learning

Most Georgians today have probably not even heard of Ida Cox---even older members of the African American community. In stark contrast, she is revered by musicologists.

The U. S. Congress had declared 2003 the "Year of the Blues," but little homage was paid to this important blues figure. Perhaps now is a fitting time to re-explore Cox's musical path and discover what makes her story worth remembering.

She triumphed despite social hurdles, racial barriers and the Great Depression.

Somewhere amid the Ida Cox journey echoes a sublime, inspiring theme, pulsating to the infectious groove of a ragtime melody, reassuring a new generation that life can surely be pursued to the fullest extent given the opportunities accessible today.

MUSIC SOURCES

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, 1923, Volume 1, DOCD-5322, Document Records.

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works 1924-1925 in Chronological Order, Volume 2, DOCD-5323, Document Records.

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works 1925-1927 in Chronological Order, Volume 3, DOCD-5324, Document Records.

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works 1927-1938 in Chronological Order, Volume 4, DOCD-5325, Document Records.

Ida Cox: Complete Recorded Works 1939-1940 in Chronological Order,

Volume 5, DOCD-5651, Document Records.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Whitney Balliett, "Talk of the Town: 'Yes Yes Yes Yes'," The New Yorker, April 29, 1961.

Robert Booker, "Ida Cox: star blues singer before retiring here," Knoxville Journal, April 13, 1989.

Jack Neely, "Whoom, Like That," Metropulse, February 1-8, 1996.

Jack Neely, "The Secret Diva of Louise Avenue," Metropulse, February 24, 2000.

Robert Santelli, The Big Book of Blues: A Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Penguin Group, 2001).

Robert Santelli, Holly George-Warren and Jim Brown, eds., American Roots Music (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001).

Bill Wyman, Bill Wyman's Blues Odyssey: A Journey to Music's Heart & Soul (New York: Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc., 2001).

"Obituary: COX, Mrs. Ida," Knoxville News-Sentinel, November 12, 1967.

OTHER SOURCES

Telephone conversation with Mrs. Edna Prather, Toccoa, Georgia, on May 23, 2003

Telephone conversation with Joseph Johnson, Georgia Music Hall of Fame, Macon, Georgia, Summer 2003

Telephone conversation with Lynn Westergaard, Atlanta, on November 9, 2003

Telephone conversation with Chris Albertson, New York, on August 8, 2008

*Special thanks to Jamie Osborn, Reference Assistant, McClung Historical Collection, Knox County Public Library System, Knoxville, for his assistance, October 2003

Author: Greg Freeman. Published May 7, 2006. Revised August 9, 2008.

Copyright

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

Southern Edition

All Rights Reserved

All materials contained on this site, including text and images, are protected by copyright laws and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. Where applicable, use of some items contained on this site may require permission from other copyright owners.

Fair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.

Contact Greg Freeman or SouthernEdition.comFair Use of text from SouthernEdition.com is permitted to the extent allowed by copyright law. Proper citation is requested. Please use this guide when citing a Southern Edition article.